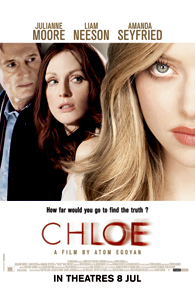

Chloe belongs to that latter category. And just over 90 minutes, it is Egoyan’s shortest thriller in a long time, the brevity distilling the essence of the plot in a well-defined and natural structure. The film’s concept is simple: a successful gynaecologist (Julianne Moore) long married (and now less happily married) to a musicologist don (Liam Neeson) suspects the latter of having affairs with his students and hires the services of a fresh-faced professional call-girl (Amanda Seyfried) to set up a sting. From there, everything unravels – but in an unexpected way as the call-girl realises how Moore seems to relish hearing the field action reports.

There’s so much that could go wrong with the film’s concept: it could have really ended as a tacky Fatal Attraction with older actors, for one. Egoyan seems to understand what the story should be about, far better than the director and writer of Nathalie..., the film which Chloe is a remake of.

First and foremost, Chloe is a character study of three different worldviews championed by its principal actors. In the soul-destroying environs of the city and suburbia, the call girl finds that one good thing in every client; the wife suspects the worst thing in her relations; the husband is the unguarded optimist. Setting them loose on each other in the film, Egoyan demonstrates the dictum that plot is simply character in motion, and that the terrors of suburban conformity don’t have to be measured in hysteria and angst.

Chloe is Egoyan’s turn at playing Douglas Sirk. If Sirk were to make a modern ironic melodrama that ultimately subverts the comfort of suburbia, the middle class, and the nuclear family, it might very well be this film.