The passing of Aleesha Farhana on July 30 brought a spate of reactions from Malaysians from all walks of life including social activists, politicians and civil society, with many expressing compassion for her suffering, and solidarity with her struggles.

In Malaysia (and many parts of the world), discrimination based on behaviours, ethnicity, race, gender, sexual orientation or social characteristics has unfortunately permeated our society, and worse, codified in civil and syariah laws.

Aleesha Farhana, a Malaysian and a transgender, was rejected in her application to the High Court to change her name and gender identity on official documents, thereby denying her right to live as the gender of her choice. Since then, while many of her peers choose to live their lives in obscurity and silence, Aleesha became a visible advocate for transgenderism in this country.

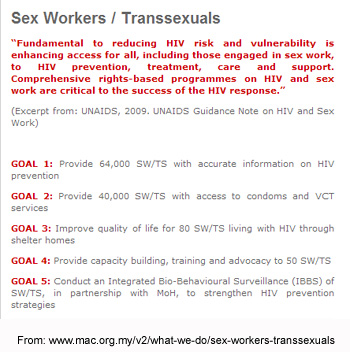

To date, several NGOs and many individuals have come out in support of Aleesha’s right to determine her name and gender, but the largest HIV/AIDS organisation in the country, the Malaysian AIDS Council (MAC), has stayed conspicuously silent on this issue. The same organisation that professes to work closely with marginalised communities including drug users, men who have sex with men, and transgenders, has chosen to ignore Aleesha altogether.

Public health in the context of HIV/AIDS is inextricably intertwined with human rights, as nearly every UN document on human rights states clear implications for HIV/AIDS. Thus, when Aleesha’s story first broke in the mainstream media, I contacted MAC and requested that this esteemed organisation extend its support.

However, the response I received from MAC was shocking.

“MAC’s focus … is strictly limited to ‘promoting and protecting the rights of people living with, and/or affected by HIV/AIDS.’ Yes, our transgender sisters are indeed one of the key populations ‘affected by HIV/AIDS’ but MAC’s purview is purely within the confines of addressing vulnerabilities…”

Is it not known that vulnerability to HIV/AIDS is heightened by the denial of rights, such as the right of transgender people to determine their own names and gender-identity? In order to reduce vulnerabilities, action must be taken to enable individuals and communities to make choices in their lives, thereby decreasing the HIV/AIDS risks to which they may be exposed. While the complexity of balancing effective human rights advocacy with maintaining a working relationship with government agencies should be acknowledged, MAC must not lose sight of the fact that the lack of legal recognition of the lived gender identity of transgender Malaysians still presents a huge barrier for them to access HIV/AIDS services in this country.

The effects of discrimination — gender-based and homophobia — in the Malaysian context continue to hamper MAC’s efforts to stem the tide of HIV infection amongst marginalised communities. Malaysia remains one of several countries in the region to criminalise male-to-male sex and transgenderism, frequently leading to abuse and human rights violations.

Correspondingly, HIV prevalence has reached alarming levels among men who have sex with men and transgender populations here. In a report entitled “Legal Environments, Human Rights and HIV Responses Among Men who Have Sex with Men and Transgender People in Asia and the Pacific: An Agenda for Action”, commissioned by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Asia Pacific Coalition on Male Sexual Health (APCOM), it was stated that criminalisation and inappropriate enforcement of legal provisions violate the rights of men who have sex with men and transgender persons, thereby obstructing advocacy, outreach, and delivery of HIV and health services, which in turn reduces the effectiveness of national HIV responses.

According to Jeff O’Malley, director of UNDP’s HIV practice: “In the context of HIV and in the context of human rights, we must continue to vigorously defend and promote rights based HIV, health and development policies and programme responses — this necessitates working to remove punitive laws and discriminatory practices.”

Is MAC then not guided by these principles, and the resolutions of the UN Commission on Human Rights, the 1998 International Guidelines on HIV/AIDS and Human Rights, and the 2001 consensus document that was issued by the UN General Assembly Special Session on HIV/AIDS? These documents provide HIV/AIDS organisations with useful tools for advocacy in relation to HIV/AIDS and human rights. In essence, the Malaysian response to the epidemic must not be constrained to only the technical and operational aspects of public health, but also include civil, political, legal, social, and cultural factors that surround them.

Similarly, the UNAIDS’s strategy to achieve universal access to appropriate HIV prevention, care, treatment and support for men who have sex with men and transgender people is anchored in three key guiding principles, the first of which is that “actions must be grounded in an understanding of, and commitment to, human rights” and that “discriminatory laws, attitudes and behaviours [that] undermine effective programming… must be challenged and revised when the opportunity arises.”

Unfortunately, the Malaysian AIDS Council, the national organisation that promises to promote and protect the rights of people living with, and/or affected by HIV/AIDS, does not share this view.

If indeed Aleesha’s death was unavoidable, at least let us not make it in vain.

Bakhtiar Talhah is a Malaysian living with HIV and former executive director of the Malaysian AIDS Council. This is the personal opinion of the writer.