Cute girls, giant robots, samurai battling ninjas, pocket monsters. The imagery is what one frequently receives when one thinks of Japanese comics, or manga (literally: 'frivolous drawing'). But there is an alternative for those searching for more realistic stories and familiar situations, aimed at a mature audience. That alternative comes under a now nearly-forgotten term: gekiga (literally: 'dramatic drawing'). It is time we remember it again, as probably the only reason why gekiga is so forgotten is perhaps due to its tremendous influence on mainstream manga, which has incorporated its sophisticated storytelling techniques and panel compositions.

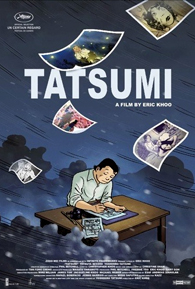

This film is a celebration of the artist credited with coining the term: Yoshihiro Tatsumi, and is based on his gekiga-form autobiography A Drifting Life, as well as adapts five of his best short stories: Goodbye, Beloved Monkey, Hell, Occupied and Just A Man. The five stories are basically episodes sandwiched in the middle of what appears to be a more-or-less straight autobiography of Tatsumi himself, who provides the narration of his struggle from poverty to his eventual success in the comics industry. Warm without being cloying or sentimental, it stands alone pretty good, but it’s the stories that truly bring to life the tremendous gifts Tatsumi is possessed of. Situations involving such elements a wartime photographer capturing a poignant image in Hiroshima’s ruins, a factory worker living with a monkey in a dingy apartment, a retiring salaryman’s search for a perfect extra-marital affair start off predictably, but play out ingeniously against one’s expectations, and still retain their watertight internal logic.

It also helps that Tatsumi’s panels, upon which most if not all shots in the film are based, contain beautifully precise cinematic compositions and layout to begin with. Khoo respects the material: his animation is spare but effective, merely serving to fill in the spaces between panels and nothing more, and giving the feel that one is watching a moving comic book rather than an animated feature.

Tatsumi joins a series of excellent animated features aimed at adults that have plied the festival and indie circuit in recent years. It belongs in the company of Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, Adam Elliott’s Mary and Max and Ari Folman’s Waltz With Bashir. Even more valuable is the breakthrough in Singaporean creativity it represents; where using an Indonesian crew and Singaporean money, director Eric Khoo makes an authentically Japanese film. It is an effort that deserves applause and a touchstone for Singapore cinema. However, while Tatsumi gives Singapore and Eric Khoo a near-masterpiece they can be proud of, one should not forget the long-overdue recognition due its subject, Tatsumi-sensei himself. His brilliant sense of storytelling, precise timing and mature, complex storylines rich in emotion and irony make him an artist for the ages, and his rediscovery is something worth celebrating.