The year was 1997. I was about 13 years old when I first accessed the Internet. One of the first things I did was look up "gay" on the Lycos search engine, to see if there were others like me. I was a lonely child in an all-boys Methodist school in Singapore. We were taught regularly that homosexuality was an abomination punishable by an eternity in hell. Rebelling against this idea, I sought solace online, only to stumble upon godhatesfags.com, a website hosting a particularly virulent strain of militant homophobia espoused by the infamous Fred Phelps, who heads the Westboro Baptist Church in Kansas, USA.

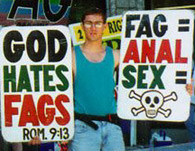

A member of Fred Phelps's Westboro Baptist Church with its signature 'God hates fags' and 'Fag = Anal sex = Death' placads.

Although Fred Phelps is peculiarly hateful, his opinion is not particularly unique. There are many who believe that AIDS is a disease that only gays get, and that we deserve to have it for the irresponsible sex we are having. As a 13-year-old, I had already been taught in school that AIDS was a gay disease, and many of the school bullies would intersperse their gay-bashing comments with references to my getting AIDS.

Though not commendable opinions, they are certainly understandable, given the history of the disease. The first outbreaks of AIDS-related symptoms were in the form of Kaposi's Sarcoma (an extremely rare skin cancer), on the bodies of otherwise healthy homosexual men. So linked together was this mysterious outbreak of these infections with homosexual men in the 1980s that HIV (the Human Immunodeficiency Virus, or the virus that can lead to AIDS) was at first called GRID, or the Gay-Related Immunodeficiency Disease. Before the development of antiretroviral treatments, many died alone, abandoned by their families and by the medical establishment, who cast suspicious eyes at the individuals who had contracted this virus. With misinformation about how this virus was transmitted, those who had it were increasingly socially isolated in a misguided effort to contain the spread.

But that was then� Perhaps.

In 2002, when I was 18, I started seeing Sh, an HIV+ man whom I met on fridae.com. It began as a harmless gratuitous heart-exchange flirtation that blossomed into a full-fledged romance. At the time, I did not know he was HIV+. At the time, I thought that I was open-minded, and knowledgeable about the disease. However, the second night we spent together, when he came out to me about his status, I was completely flabbergasted. I could not contain my tears and my rage. I started accusing him of wanting to kill me, accusing him of premeditating his declaration with the intent of hurting me. He was a bad person. Sick. Pervert. All of my insecurities and internalised homophobia exploded out to destroy the man whom I had just a few moments prior called "my love."

I can only imagine the depth of pain I must have caused him from my own ignorance. Our relationship, fortunately, lasted much longer than my tumult of hyperbolic spew. After I calmed down, I realised how terribly I had behaved, how mean-spirited I had been. After all, we had always been safe.

In an effort to develop my own understanding, I began volunteering for the Action For AIDS Singapore, a volunteer-based organisation in Singapore that provides HIV-education and anonymous HIV-testing. There, I was exposed to a gay community beyond the hedonism of the club scene, and beyond the shy safety of being behind a computer screen. I learned not only the importance of HIV-prevention, but also of reducing the stigma against people who were already living with HIV/AIDS.

As it is, at the moment, there is no cure. And at the moment, it seems that part of the reason HIV is taboo is because of its association with forbidden and taboo subjects, such as homosexuality, sex work, women's sexuality, drug use, poverty and black Africa, as well as its associations with being concentrated in very specific human fluids (blood, semen, precum, vaginal fluids, and breast milk). Not a topic to raise in polite company.

Perhaps the most poignant reason that HIV/AIDS has been such a difficult topic has been its association with death. That night that my partner came out to me about his status, I was swamped with so many fears of death. I thought that if he had infected me, I was going to die. I thought that he was going to die, and that was why he was telling me. I figured that no matter what, our relationship would forever be tainted by the smell of frangipani, as death loomed large over our heads. We were two gay men in a gay relationship, and one of us was HIV+. What would everyone think?

After all, in our society, the burden of hetero sex is associated with the creation of life (through unwanted or unplanned pregnancy), whereas the burden of gay sex is associated with the destruction of life (in the transmission of HIV, the virus that leads to AIDS, and the inevitable breakdown of the human immune system from the syndrome, leading to eventual death). In a way, Fred Phelps did not need to tell me Fag = Anal sex = Death. I already knew that.

Over the next few months of our relationship, Sh and I spoke openly about our fears. He spoke about his fear of hurting me, infecting me. I spoke about my fear of what this might mean for us in the long term. We confronted the reality of death, and simultaneously, we spoke openly about what did and did not feel safe for us to do together sexually. We pursued the path of open communication. I fought against the idea that AIDS = Death. Instead, I adopted the slogan "Silence = Death," developed by the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), a group that started in New York City which has historically used radical methods of civil disobedience to bring attention to the impact of AIDS on disenfranchised communities. In order to address HIV/AIDS, we have to talk about sex. We must not be silent.

Many gay men have seen their close friends die of this disease, but this, in a way, is hardly a unique experience of the world. Tragic as it may sound, the mobilisation of our communities around the issue of HIV/AIDS could perhaps even be seen as a blessing for us; it is a way that our community has had to confront the philosophical problem of death, something that heterosexuals categorically do not ordinarily consider. If HIV led to AIDS, and AIDS was synonymous with death, then confronting HIV meant confronting the reality of the inevitability of death and the implications of this consideration on our sexual identities. The appalling disinterest of governments worldwide in tackling this issue from the outset, and the stigmatisation of people living with HIV was and is, to me, partially symptomatic of a universal human anxiety regarding the issue of death. After all, death does not only happen to those who have AIDS; it is life's only inevitability for all of us, gay or straight, Asian, African or European, rich or poor, male or female, drug user or sober Puritan, religious or atheist. Far from being morbid, it is realising and confronting our own mortality, the inevitability of our death, that becomes the root of developing wisdom. In order to address HIV/AIDS, we have to talk about death.

It has been a few days since World AIDS Day, which was on December 1. It might be helpful to reflect on where we are at in the world with regard to the epidemic. The face of people living with HIV/AIDS on the planet is rapidly changing. Within Western countries, rates of HIV transmission from anal sex between men have been relatively stable, although many young men in my generation are becoming increasingly complacent about practicing safer sex, thinking ourselves immune, and rates of new infections among men who have sex with men are climbing again. Incidences of HIV-transmission are now increasing most rapidly from the sharing of contaminated needles (of drugs, hormone injections, etc.), from mothers who are HIV+ during childbirth, and both heterosexually and homosexually transmitted all across the Sub-Saharan African and Southeast Asian continents from a lack of awareness and access to education. AIDS-related mortality rates are especially high in populations who do not have access either to preventative education or to antiretroviral medication, and AIDS-related deaths has arguably been the single most significant deterrent to the economic progress of Sub-Saharan Africa in the past few decades, claiming the lives of millions of men, women, and children, and debilitating millions more who live with the disease. At the same time, in more privileged countries, we may begin to see the first few generations of HIV+ adults who were born with HIV, and who may have lived with the virus their entire lives on medication. They will certainly become interesting spokespeople living with HIV in the years to come.

I broke up with Sh when he came to visit me in college in 2004. We had been together for two years. Thankfully, I was still HIV-. As all heartaches can be, ours was no less complicated. But it was impossible to end our relationship with any animosity between us, from all that we had shared together. Our parting had nothing to do with his HIV, but it would be a lie to suggest that it had not affected our relationship all along. HIV had made us speak more openly about sex and desire, love and longing, fear and insecurity, life and living, death and dying. In a way, HIV had helped to bring us closer. We parted crying our bittersweet tears on my small town college campus, renewed in our commitment to living our lives to the fullest apart. We had both been transformed.

As we kissed goodbye, I could taste that sickly sweet smell of frangipani that had hovered in the air of our relationship. It was turning into lavender.

Malaysia-born and Singapore-bred Shinen Wong is currently getting settled in Sydney, Australia after moving from the United States, having attended college in Hanover, New Hampshire, and working in San Francisco for a year after. In this new fortnightly "Been Queer. Done That" column, Wong will explore gender, sexuality, and queer cultures based on personal anecdotes, sweeping generalisations and his incomprehensible libido.