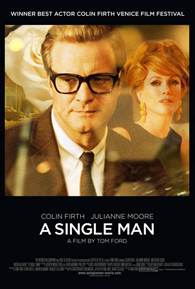

For everything, there is a season; for English Prof George Falconer (Colin Firth), it is time to call an end to it after a protracted period of mourning for his late lover. On an otherwise unremarkable day, he will perform each task to perfection, tying up loose ends at work, saying subtle goodbyes to his neighbours and his best friend and almost wife Charley (Julianne Moore), and taking one last look at all the hunks and twinks in his college. And then, he will kill himself...

Vernon says...

The Greeks were all-rounders. They were interested in how to lead a good and meaningful life, but they paid equal attention to how to have a good, meaningful death – at the conclusion of a full life. They even had a term for it: euthanasia. Life and death are hence understood as dependent on each other, giving meaning to each other.

Christopher Isherwood understood this principle when he wrote his novel, and Tom Ford grasps the point as well. If Colin Firth’s English don is shell-shocked to the point of emotional stasis or an almost unbearable mannered disinterest, an eloquent lyricism arises from its flashbacks, which are accompanied by Firth’s narrations.

The film captures the mentality of grief and mourning, but is ultimately an optimistic meditation on life and its little surprises and distractions. At each step of his journey towards suicide, Falconer’s world literally lights up and moves from a desaturated palette to full colour, as he connects (however briefly) with other strangers and friends.

Tom Ford appears to have far less confidence in his material than he should, and overcompensates by drenching the film with an excess of style – a syrupy soundtrack, constant and unsubtle playing with colour palettes, slow motion freeze frames. Every mistake in art direction that a first-time director can commit, he does. This is a beautifully made film, but the beauty wears off with overuse, and then turns annoying, if not ugly.

A little over-sentimental, A Single Man plays like a conventional cousin of Le Temps Qui Reste, which explores the same issue of euthanasia from a more daring and emotionally convincing angle.

Caleb says...

C.S Lewis, in A Grief Observed, his marvellous meditation on the anguish and suffering of losing his wife, nicely encapsulates George Falconer’s position in this movie: “I not only live each endless day in grief, but live each day thinking about living each day in grief." Falconer chooses to end this incessant self-reflective suffering with a revolver.

Colin Firth is quite wonderful as Falconer, giving a quietly powerful and very measured performance. It would have been easy to descend into cliché playing the gay sardonic witty English Lit professor, but Firth is far too good an actor for that. Mixed in with the resigned fatalism and verbal barbs is a playfulness expressed primarily in flashback, but also in little glimpses during the course of his day, perhaps suggesting he is not quite ready for death.

A pity then that many other aspects of the movie were not quite so subtle. Given that fashion designer Tom Ford is the director, it is a surprise that in many ways art direction was the weakest aspect of the movie. While the 1960s set and décor were wonderful (brought to you by the same people who designed Mad Men), Ford’s decision to shoot much of the movie in muted tones (no doubt to personify Falconer’s grief) is patently transparent and lacks nuance. Random scenes of Falconer floating naked in the water were not only bizarre but completely out of place. Julianne Moore was also completely over the top as Falconer’s sometime lover and best friend, complete with fake upper class London accent.

T.S Eliot claimed that the world ends not with a bang but with a whimper. Grief too is similar – its true tragedy comes in the transformation of the everyday and familiar into objects of agonised longing. Too bad Tom Ford never really grasped that.

Consensus:

A Single Man is a pretty good film for a first-time director, though it is not so easy on the eyes as you would expect.