“The whole conviction of my life now rests upon the belief that loneliness, far from being a rare and curious phenomenon, peculiar to myself and to a few other solitary men, is the central and inevitable fact of human existence.” – Thomas Wolfe, “God’s Lonely Man”.

Meet Beto (Nolberto Coria). He is a small and unremarkable man. His existence is a monotonous and routine one. He boils his water. He prepares his food. He reaches out into the street to buy his tamales, occasionally he finds himself having a bit of sex with a homely prostitute (Tesalia Huerta). Beto is the custodian of a house on the outskirts of Mexico City, and takes care of it for a rich woman that he’s vaguely acquainted with. The other servants do not speak of him.

Ensconced behind the walls of his suburban redoubt, he sometimes listens to the radio broadcasts, which speak to him of the horrors of the world outside with its murders, robberies and kidnappings. His expression is one of indifference for the most part. And it is always not long before he is back to his routines.

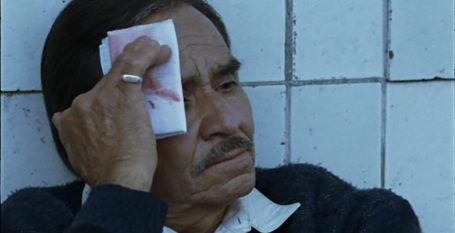

As played by Nolberto Coria, who supposedly does live a life similar to that of his character, Beto is a cipher for much of the movie. With a weathered, leathery face that is also a stoic and unchanging mask for much of the film, Beto says however, that he cannot live with anyone else, but we doubt it and wonder what other truths might lie under the stoic mask of skin that is his face. Is he actually able to bear his profound loneliness, if it does, what does his loneliness really mean to him?

The film might be an argument for that being beside the point, for Parque Via is a study of characters who live with a profound loneliness. A scene early on demonstrates that Beto is not alone in his loneliness. The prostitute also does “dance partner” gigs, in which she is paid a sum in order to dance with any man who chooses her as her partner. The camera concentrates on her face as it happens, showing the weatherbeaten indifference for whom the answer to whether is that all there is that it is all there is.

Most of the film maintains a hypnotic rhythm underneath its routine and repetitious exterior. When the devastating finale hits, it is almost worthy of comparison to Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver”. It is one that makes you wonder what more you ever needed, or wished you knew, about those individuals that fade into the cracks of society.