The bargains we make with our own devils to gratify our inmost desires are the stock of fiction, and much of it good fiction at that. Who has not heard the words of the Bible –“For what shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?” – and who has not ignored them? Stories of the characters who do exactly that resonate as eternally in our mythology as they do in our consciences, principal amongst them, of course, being the German Faust, who famously provided a theme for Christopher Marlowe and Goethe, and was the inspiration for Thomas Mann’s composer Leverkuhn. Oscar Wilde gave us Dorian Gray and the portrait that bore his corruption, a character who is still very much with us on screen and page, most recently in Will Self’s rendering, Dorian, whose decaying visage is incarcerated in a video programme run on nine screens. Modern but no different is Self’s enfant horrible, whose intent is "to display talents in the only two areas of human life that are worth considering: he was becoming a seducer par excellence, and he was transforming himself into an artificer of distinction, a person who is capable of employing all of the objective world to gain his own end." Narcissus personified, and, as all these morality tales tell us (even that of the cynical Will Self) such sinners always get their just desserts.

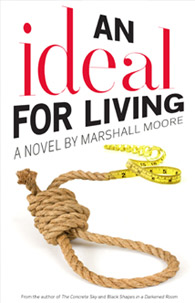

Or do they? Marshall Moore is none too sure, and his thoroughly modern novel, An Ideal for Living, gives us another answer. Moore is an American who has settled in Hong Kong and is now making a living here as a publisher. He has two other books in print: The Concrete Sky, a novel published by Haworth Press in 2003; and Black Shapes in a Darkened Room, a collection of short stories published in 2004 by Suspect Thoughts Press. Like An Ideal for Living, Moore’s first book centred on a gay character but could not really be classified as a “gay” novel, if such a thing really exists, as it focused on the psychological traumas affecting a man whose homophobic brother instigates his incarceration in a mental institute. Similarly, Moore’s new work has a gay perspective, for one of its two major protagonists, Robert, is gay, but this story pulsates like two binary stars around the state that he and his heterosexual sister, Grace, find themselves in when, due to chronic obesity and its accompanying depression they can get laid respectively by neither boyfriend nor husband. The siblings live in that ice cream cone of bodily beauty, northern California, and so find that they have eaten themselves into a state not only of sexual frustration but of social pariahdom. Here is Grace checking into the spa which is to prove yet another failed attempt to remove the pile of discarded tyres she carries, walking past other women guests, thin ones:

The four women giggled again, almost out of earshot now. This time the brunette turned back and sent a nauseating look of pity Grace’s way. Grace stopped cold and would have screamed if there had been any emotion left in her. The only hourglass figure she felt like seeing at the moment was the red one on a black widow spider’s back just before she dropped it down this bitch’s dress.

Unsurprisingly, Grace and Robert will do anything to fight their way back to the beauty that they just know is within them. It is Robert who stumbles on the answer: Stefan, a character with indefinable wisps of somewhere in central Europe, whose deft, magical hands can not only evaporate flab but can touch and mould flesh into a beauty that was never there before. Who is this modern Californian equivalent of the kind of Filipino faith healer we have all seen featured on cable TV? Robert neither knows nor cares, and although, to get what Stefan has to offer, he’s prepared to pay as much as is demanded of the mega salary he earns as a semi-successful corporate lawyer, he’s more than reassured with Stefan’s blandishing reply: “You can afford it.”

This is a very sassy, clever novel, outrageously funny on almost every page, and one that uses the failings of the zeitgeist to make us laugh as we are appalled. Here is Robert in a scene reminiscent of that classic shot in American Pie, as James, perennial just-out-of-reach object of Robert’s lust, tells him “I don’t think sperm mixes well with styling gel. I think it forms a cement, and you have to cut out that part of your hair. If there’s a patch of my hair missing the next time you see me…” “It’s because you had dim sum? I thought you weren’t into Asians.”

Yet the slick, cynical, parodying surface gloss of this novel, just like Wilde’s and Self’s, hides a chilling core, the realisation that, for these characters, the satisfaction of desires, no matter how trivial, excuses all grossness, all the evil they are brought to contemplate, and that even the love for which they think they are doing all this is nothing more than self-gratification. When the ultimate price for the beauty of Robert and Grace’s souls comes to be paid, they can indeed afford it, for it is paid by other people.