Adam Sandler comedies are easy to hate despite the money they make, or because of the money they make. It's not so much stemming from the fact that Sandler's trademark persona is a basically a socially-maladjusted manchild with asshole tendencies since after all, great comedians have always trafficked in misanthropic personas. Rather it's the fact that Sandler's attitude towards his character is always one of condescension ("'Ha ha, look at him, isn't he SILLY?") when it isn't outright contempt towards the audience ("Look at him, he's such a jerk ass, but he's so successful and gets the girl anyway, isn't that SWEET?"). By refusing to make his characters underdogs, Sandler glosses over what comedians since antiquity always tacitly acknowledged: misanthropic characters are fun to watch only because their exaggerated flaws also render them outcasts. In most Sandler comedies, his characters do go through the necessary challenges to win their sweetheart, but in most cases there's never an acknowledgement that his characters remain fundamental jerkasses till the end, so the contempt for the audience stays.

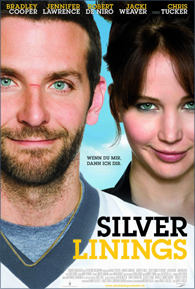

In Silver Linings Playbook, our socially-maladjusted manchild with asshole tendencies is embodied in a brave performance by chiseled leading man material like Bradley Cooper, who of course flies in the face of movie logic that socially stunted man-children are roles for ugly guys. Cooper plays Pat Soletano, a bipolar former teacher who catches his wife Veronica (the long-dormant Julia Stiles) with a colleague, clobbers the shit out of said colleague, and is sent to a mental institution afterwards after a restraining order is placed on him by his wife. Released from the mental institution by his well-meaning mom (Jacki Weaver) though not completely well yet, Pat is upbeat and chipper about the course of recovery his life (thus the title, for he believes every cloud has a silver lining) is going to take by patching his relationship up with his wife, but it's not long before he gets into more trouble again. Mom probably has a long suffering history of dealing with obsessive men: Pat's father (Robert De Niro) is a Philadelphia Eagles fan who makes a living apparently as a bookie for the team after he lost his pension. The brilliance of this setup immediately destroys the comfortable assumptions underlying the Sandler formula that misanthropic personality disorders need not be a hindrance to personal or relationship success, and of course by having a flawed father figure who may be as dependable as our protagonist at the same destroys the notion common to such films of father figures as quirky but ultimate sources of wisdom.

Pat is drawn to Tiffany, a troubled young widow in the neighbourhood (Jennifer Lawrence) partly out of desperation. Jennifer Lawrence as always is phenomenal as well and her character just makes this movie as great a break from Sandler's insipid executions of similar material in the best way it can. The hot chick in Sandler films is in general part of a long line of clueless wallflowers who seem to be there as the victim of pranks by the object of their blind affections, and apparently are the only characters in the film's universe who find the protagonist charming and faultless. It's therefore great to see Jennifer Lawrence play a damaged, but active and tough chick who takes no guff from Pat even as they slowly come together and heal each others' wounds, and is clearly the stronger partner in their relationship. Just like in a Sandler movie the eventual challenge is mainly the chance for the main character to engage in a bit of silly physical comedy, and here, it arrives in the form of a dance competition that Pat and Tiffany take part in, but not without more hilarious complications on the way.

Other than De Niro, the other supporting players turn in great work. Dash Mihok plays the usual clueless cop with a heart of gold, while the token minority roles are filled by Chris Tucker, now fatter and less motormouthed, as Pat's fellow patient friend, and Bollywood veteran Anupam Kher as the stereotypical Shrink of Asian Origin.

David O Russell's tight and intimate direction draws you well into the characters and their struggles, and gives their conflicts a vibrant raw immediacy. His screenplay, based on a novel by Matthew Quick, transcends its Apatow/Sandleresque roots to become a critique at American over-optimism which is perhaps at its heart, a childish unwillingness to face reality and that sometimes it just isn't fair. It's most telling that the victims of his critique are mostly men, leaving his female leads to become the film's anchor in sanity. Russell has made a comedy that draws its laughs from male neuroses to critique them, and by doing so, exposes the hollow assumptions that the 'manchild comedy' formula is built upon.