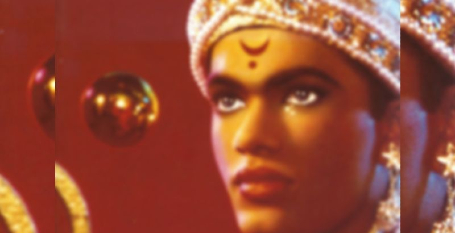

We caught up with Ash Kotak for a behind-the-scenes look at his play, Hijra.

What’s the background to Hijra?

I wrote Hijra in 1998, at a time when it was illegal to be gay in India – due to a left-over British colonial law. I would see the Hijra – trans women who live in communities led by their Guru – dancing and prancing at my cousins’ weddings in small town India. It seemed hypocritical that under Hindu beliefs the Hijra were venerated yet feared – they had the power to offer good luck or cast spells of bad luck depending on your reaction towards them.

I was young and exploring who I was. So, I wrote a comedy based on the Gujarati theatre style I knew so well from Mumbai, and also in the UK.

Knowing that the issues I was discussing in Hijra were considered inflammatory and even distasteful, I wanted a recognisable style. I desperately wanted to speak more directly to my own community.

Hijra was an immediate hit, it had great reviews in all the nationals. I was too naive then and perhaps too optimistic to predict what a negative backlash there would be from my community. I was attacked for writing a gay romantic comedy. It nearly destroyed me.

Why is Hijra a story that connects with audiences?

Hijra is a cross-over play. The Bush theatre were stunned at how the first production sold out quickly, and how diverse the audiences were. This has been the case for every production.

Hijra deliberately taps into that universal human desire to belong, to be part of a community, and the powerful urge to love and be loved. This is juxtaposed by the internal pull to be yourself, and the necessary growth and value-shift required to marry both ideals.

Hijra is a rom-com, but also a modern day Restoration Comedy. It worked and brought in new audiences. It’s unashamedly commercial. My parents came. Other South Asians came. Women in their saris sat next to women in Burkhas who sat next to all types of Queers. It was written to be a great night out.

I’d learnt as a child sitting in the wings, that the form of a play utilised by a playwright was very important in order to connect to the audience that they wanted to reach. I guess I wanted my parents to understand and accept me, as I am. I guess I wanted to be accepted by British Queers. It was a time of new hope and a new millennium was imminent.

When was the last time that Hijra was staged?

Hijra was last performed in San Francisco in 2006, when it won a Bay Area Award. At around the same time, it was translated and published in French and toured France and Belgium. It worked particularly well there.

Is Hijra a play that still works in today’s context?

The law may have changed in India, but attitudes will take a long time to reform – it requires a change in values, and that takes much internal work and time. Our communities import their prejudices from the Indian subcontinent. British Queers from Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka still have many battles to win. Their struggle is huge.

Many of us LGBTQ South Asians, of my generation, who pushed for our own visibility in our communities as well as in British Queer society, took a battering. We had a lot to fight against – there was AIDS, there was our collective shame, there was homophobia. But we had to deal with racism and, of course, the burden of failing the dreams of our immigrant parents. I had to forge a new British and at the same a new Indian identity if I was going to be happy and if my life was going to be valuable to me. It caused huge clashes from all sides.

Today, I look at 20-something Queer South Asians with pride, like an uncle, seeing them fighting for their own visibility now. Not much has changed, really. I hope they don’t go through what many of us in my generation went through. I hope they find love and happiness and acceptance. We all learn from each other.

I want that generation to know what we were doing. Hijra summarises the time very well, I still believe that.