On 1 Dec 2006, Norway, together with 54 other countries, delivered a statement in the United Nations expressing deep concern on human rights violations based on sexual orientation and gender identity. Soon afterwards, the United Nations granted consultative status to three LGBT non-government organisations, giving them standing to speak in the assembly on sexuality issues. These developments are greeted by international LGBT organisations as significant victories against state homophobia.

At about the same time in Singapore, the government is considering amendments to its penal code which originally criminalises anal intercourse for all, to one that will criminalise anal intercourse only if it is between men. In other words, it is, in effect, considering singling out gay men for discriminatory treatment under the justice system. If passed, it will create a precedent where the law need not treat every citizen equally but can discriminate against a particular group.

152 countries have signed this covenant. Asian signatories include Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, North Korea, India, Indonesia, Japan, Laos, Mongolia, Nepal, Philippines, South Korea, Thailand and Vietnam. This demonstrates very clearly that respect for human rights is a universal value. By remaining the last few countries that refuse to sign, Singapore is keeping the company of countries such as Malaysia, Myanmar, Indonesia, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia.

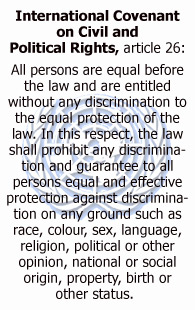

The power of this UN covenant was put to the test in 1991, when an Australian by the name of Nicholas Toonen, complained to the UN human rights committee that Tasmania's law criminalising homosexual sexual acts has violated its provisions. He submitted that the laws violated his rights under article 2 (discrimination based on his status as a homosexual man), article 17 (privacy) and article 26 (equality before the law) of the covenant. He argued that the wording 'other status' in the covenant includes homosexuality, that the state has no business interfering with what he does sexually in the privacy of his own home, and that the Tasmanian laws also violated the covenant on account of equality before the law since it singled out gay men. The Australian Federal government agreed, saying of the criminalisation of anal sex between men: "While they specifically target acts, their impact is to distinguish an identifiable class of individual and prohibits certain of their acts. Such laws are thus clearly understood by the community as being directed at male homosexuals as a group." In its findings, the UN human rights committee notes that prohibition against discrimination based on sex includes sexual orientation, and concluded that the Tasmania law does violate Toonen's privacy rights.

Another parallel with Singapore is that Tasmanian authorities tried to use the moral argument to justify the law. Toonen rebutted this view in his submission: "Australia is a ģ multi-cultural society whose citizens have different and at times conflicting moral codes. In these circumstance it must be the proper role of criminal law to entrench these different codes as little as possible; in so far as some values must be entrenched in criminal codes, these values should relate to human dignity and diversity."

As a result of Toonen's submission to the UN, Tasmania eventually repealed its anti-gay laws in 1997.

One key reason why Singapore is able to continue practicing state homophobia is because it is not bound by the UN covenant on civil and political rights. This covenant recognises wide ranging rights of the individual. Some of these are: the right to life (i.e., limits the use of death penalty), protection from torture and degrading treatment, protection from arbitrary arrest and detention, freedom of expression, religious freedom, and right to peaceful assembly and association. Unfortunately, due to long-standing distain from local politicians, "human rights" has for a long time been a dirty word in Singapore.

Let's put aside the fear for a moment and ask ourselves: Is Singapore so unique that it, together with a handful of Muslim and/or totalitarian states, is somehow rightfully exempt from respect of human rights? If you think more about it, you will also realise that oppressions are inter-linked. The denial of the right of homosexuals to love is linked to the denial of many other rights for everyone. Gay equality is not a narrow gay issue, but part and parcel of universal human rights. To pretend otherwise is to short-change ourselves.

The result of this short-changing is there for all to see. More than 20 years of experience has shown that eschewing this international dimension by limiting civil society action within the geographic borders of Singapore had been largely futile. This is why so few gay men and lesbians spoke up against the proposed amendments to the penal code. It is not because people don't care, but because they don't believe it will make any difference. A fundamental re-think is imperative or the project to de-stigmatise homosexuality will further dichotomise into a small group of vocal minority activists feeling unsupported, and a large gay silent majority feeling disempowered.

Perhaps it is now time for gay rights to break out of the ghetto. We must disabuse ourselves of the myth that gay rights is merely a minority issue about sex, and embrace the realisation that it is a majority issue about respect for all fundamental human rights. It is not just about gay men's right to anal sex, but about every individual's right, regardless of sexuality, to love, self-expression and equality before the law.

Dr Tan Chong Kee holds a Ph.D. in Chinese Literature from Stanford University in the United States and is one of Singapore's best-known figures in civil society activism.