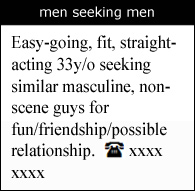

I admit it: Most of the guys that I have been attracted to can be thought of as "straight-acting." At the same time, while I don't have a problem with the set of attributes that people usually demarcate as "straight-acting," I have a problem with the term itself.

Straight-acting men and femme women

Precisely the issue!

The straight-acting guy does not "go with" anyone! He is entirely self-composed, individualistic. He is not defined either in opposition to or even mutually with "gay-acting" guys in the way that "butch" and "femme" are mutually defining and stereotypically coupled together. He is defined by something elseģ but what exactly?

Sometimes butches and femmes are accused of "mimicking" heterosexual gender norms and values (with the butch playing the "man" and the femme playing the "woman"). However, many butch and femme women retort: How presumptuous to assume that butch and femmes are "imitating" straight people! As if butch/femme are not expressions of gender and sexuality in their own right! Butch/femme are no imitation, certainly not necessarily of the values of straight men and women; Imitation of straight people? Pfft!

On the other hand, there is pride behind being a straight-acting man, pride behind its precisely imitative quality. It is straight-acting. It is an imitation, an act to mimic straights. It therefore, does not only or even primarily mean "masculine." It means acting heterosexual. "Straight-acting" comes embedded within its meaning a whole host of other connotations of which masculinity may be but one. Our desire to be straight-acting may be related not just to our valorisation of masculinity, but also a rejection of femininity, as well as coming from an implicit internalised homophobia. How often have we seen the term "gay-acting" used with pride?

Historically, gay men have not really seen ourselves fit to eroticise each other. The concept of a gay "culture" would have been elusive and absurd for many of us, growing up in eras, countries, or locales far removed from a connection to others "like us." Other openly gay men may have been seen as competition for a straight man's attention, rather than as potential partners. The men we might come to love would usually be heterosexual men whom we knew could never love us in return, and our entire sexuality may have been wrapped up and suffused with a sexuality of distance, charged with the eroticism of absence, unattainability, and sometimes, the threat of violence. Our orgasm was conditioned by our learning to eroticise this experience of disconnection.

Not that the situation for lesbians has been too different. However, there is a principle difference, which is that lesbianism seems to have been conditioned in part by a camaraderie and friendship with other women (gay and straight) that has not principally or exclusively been sexual in nature! Lesbianism and feminism found a home in each others arms from the very beginning. Much expression of lesbian sexuality has resulted in as much an assertion against heterosexual norms as an assertion of independent womanhood, which challenges the order of male power that has typically put women "in their place," (in a position of what lesbian feminist writer Adrienne Rich describes as "compulsory heterosexuality," tied to the erotic whims of men).

So straight-acting gay men are not the gay male equivalent of femme lesbians. No. They are something else entirely. The glory of an emerging visible gay culture, both locally and globally, is in how this showcases and highlights our ability to love each other, and not just define our desire by insatiability, insubstantiality, and pathology. In other words, as a gay man, I can love other gay men, and I can learn to snap out of a pattern of falling in love only straight men. However, there is still a lingering melancholy in our gay community regarding our own homosexuality. Perhaps the next best thing to loving a straight man would be loving a straight-acting man? At least this way, we might be loved in returnģ

More compassionately, perhaps this may be a survival mechanism for us in a world that continues to be hostile to gay expression. At the same time, I am uncomfortable with how lusting after "straight-acting," at the same time disproportionately rewarding straight men for playing gay roles, such as Sean Penn in Milk, and Jake Gyllenhaal and the late Heath Ledger in Brokeback Mountain (no matter how splendid their performances!) may be complicit in maintaining this very hostility toward gays.

Convert, Pass, Cover

In 2006, Kenji Yoshino, a gay Japanese American civil rights lawyer and legal writer published Covering: The Hidden Assault on Our Civil Rights, in which he methodically dissects the way society has treated racial and sexual "otherness" in the course of American history.

Regarding gay civil rights in America, Yoshino suggests that our first struggle was to combat the pressure to convert. In other words:

Gay = Bad/Wrong.

If I am gay, I am bad/wrong.

Hence I must not be gay at all, either in practice or identity.

I should convert to be straight.

This tremendously awful pressure has led to many terrible "therapies" and "treatments" for gay people, ranging from the comparatively tamer psychotherapies (ex: counselling) to electroshock convulsions and lobotomies, to mandatory castration of gay men, in an attempt to "cure" us of our homosexuality.

When that proved to be pointless, and when many of those therapies (in America) had been outlawed, our next struggle was to address the pressure to pass. This means that we may recognise that some core aspect of our identities is fundamentally unchangeable (or not convertible), and we hence experience the pressure instead to "pass," to never be found out, to live our lives in secrecy, and to convince people that we are straight.

I suspect that many of us, especially in gay Asia, are still in that experience of our sexual identities. Many of us may be out to our friends, but not our families or our workplaces. Harvey Milk, the first openly gay man elected to public office in the USA, on whom the recent film Milk is based, famously said, "If a bullet should enter my brain, let that bullet destroy every closet door." Those words can be interpreted as Milk's desire to overcome the pressure to pass, and come out from hiding the reality of who we are. After all, it is only in our visibility that we provide a first step for people understanding the reality of our humanity. However, as Kenji Yoshino demonstrates, even if we did that, there is one more pressure: The pressure to cover.

Yoshino defines covering: "Covering" is a term used to describe "the way we try to 'tone down' stigmatised identities, even when those identities are known to the world." To cover means that we work around the assumption that people may accept and maybe even embrace that we are gay, but these very same people may be uncomfortable when we do gay. For example: Even if our family, friends, or workplace know that we are out of the closet, and are comfortable with that level of disclosure, they may be uncomfortable if we want to bring our partner(s) to a work party, or a family celebration, or if we want to get married or hold hands in the shopping centre. Basically, we can be gay, but we should not act gay, or even publically associate with other gay people!

The pressure to convert, the pressure to pass, and the pressure to cover. Yoshino has given us a good vocabulary to examine where we are at in the phenomenon of living out our otherwise marginal identities in the world. Of course, these pressures do not necessarily exist in a linear or progressive fashion, and any one of these pressures can be present in different places at different times, or even alongside each other. Many of us struggle inside ourselves to negotiate between the pressure to convert ("I hate myself, I don't want to be gay") and the pressure to pass ("ok, so I am gay, but I don't want anyone to know").

The phenomenon of the term "straight-acting" arises in response to the pressure to cover ("ok, so I am gay, and you know, but I'm not like other gay people").

I do not have a problem with the attraction to straight-acting people or for that matter, attraction either principally or exclusively to any type of person (whatever race, gender, height, weight, etc.) I am neither that boring nor that judgemental, and ultimately, it would be such a pointless conversation, since I have neither the desire nor the power to alter our attraction to others. I am more concerned with uncovering how our desires may be conditioned partially by the pressure to cover the more socially dubious aspects of our lives, such as our lust for sex or our need to be publically affectionate, so that we can pass as "normal." To put it most simply, I may be comfortable being attracted to straight-acting guys, but I am not likely to be too impressed with guys who call themselves "straight-acting." Hypocrisy?

There are no easy solutions at the moment. All I need to know, is that when it comes down to it, no matter how "straight-acting" you are, and no matter how "straight-acting" you call yourself, when the lights are out and our lips quiver to meet, we better both start acting really gay.

Malaysia-born and Singapore-bred Shinen Wong is currently getting settled in Sydney, Australia after moving from the United States, having attended college in Hanover, New Hampshire, and working in San Francisco for a year after. In his fortnightly "Been Queer. Done That" column, Wong will explore gender, sexuality, and queer cultures based on personal anecdotes, sweeping generalisations and his incomprehensible libido.