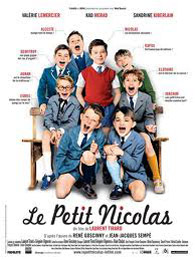

Le petit Nicolas, based on a 1959 children’s book by Rene Goscinny and Jean Jacques Sempe, takes place within this milieu, at the most ideal stage of childhood; before turbulent adolescence kicks in and school, friends and the neighbourhood are what your entire world consists of. Nicolas grows up in a comfortable bourgeois home with a salaryman father (Franco-Algerian actor Kad Merad) who works in one of those faceless upper middle management jobs in the Moucheboume Corporation and a housewife mother (Valerie Lemercier). An attempt by Dad to impress the Boss, Mr Moucheboume, by inviting him over for dinner, becomes misinterpreted by Nicolas as an attempt to get rid of him by having a baby brother, like the parents of the fairy tale character Tom Thumb did. With his diverse group of friends including the gluttonous Alceste, the scheming nerd Agnan, the slow-witted Clotaire and the tough Eudes, Nicolas attempts to find a way to stop his parents’ nefarious plan. Only to invariably screw things up at every conceivable point, with a few minor triumphs along the way. Meanwhile, at school Nicolas and his friends regularly upset their devoted but long-suffering teacher, and regularly succeed at angering the comical disciplinary head, Old Spuds.

Le petit Nicolas is a refreshing children’s film that manages to work even if you’re not a child, for it is partly about how childish modes of behaviour and expectations never seem to leave us behind. The children are resourceful but generally clueless about the wider world outside their limited circle, but adults fare little better, especially compared to the Father Knows Best universe that their American counterparts generally operated in at this time. It takes long for Nicolas and his friends to wise up to what is really happening around them, just as Nicolas’ parents can’t really wise up and move beyond their limited consciousness of Class when they have to prepare a dinner for Mr Moucheboume, just so Dad can fulfill his own fantasy, in its own way as unrealistic and far-fetched as Nicolas’ own fantasies of abandonment, of being promoted to the company’s higher echelons.

While its production design and costumes mimic the pastel feel of 1950s family sitcoms, thankfully the story is far fresher than what most American sitcom spinoffs, like the awful Leave it To Beaver reboot from the mid-90s, suffer from. Rather than deliver any moralistic angle as one might expect, director Laurent Tirard and his scribes approach the material as a comedy of manners, with both the French bourgeois and childhood dynamics among boys its equal targets. The result is while lightweight, remains a family film that genuinely feels like one, where the whole family can watch rather than just having it be a baby-sitter for the young.