When the first Singapore Biennale opened in 2006, we grabbed the chance to interview some prominent gay artists in the event. The second edition came out in ‘08, and we scored an interview with a major lesbian artist.

Then two weeks ago, the third Biennale opened, with a whole tribe of openly queer artists on show, including Singaporeans Michael Lee, Ming Wong and Genevieve Chua, the Danish/Norwegian collective Elmgreen & Dragset, the American Lisi Rankin, the German Julien Gothe and the Englishman Phil Collins.

There was, however, one artist I absolutely had to interview. This was Simon Fujiwara: a young, rather handsome Japanese-British artist who’d been making waves in the art world with his exquisitely perverse artworks – he’d just won the 2010 Cartier award for a work called Frozen at the Frieze Art Fair, detailing plans for a proposed Museum of Incest.

Folks were pretty impressed with the Biennale’s curation of Fujiwara’s new work, Welcome to the Hotel Munber. He’d dressed up a room in the Singapore Art Museum to resemble a stereotypical Spanish hotel bar, but amidst the barstools and wine and bullfighting equipment, he’d hidden items of gay pornography: nude magazine images and chapters of erotic fiction about masturbating into Spanish omelettes.

He’d explained the background to the work in a lecture performance during the opening weekend. He’d tried to write an erotic novel about his parents’ days running a hotel in Spain under the military dictatorship of General Franco (1939-1973), and how he’d tried to cast his own father as the gay protagonist. (That lecture had to be the first time we’ve had photos of gay sex acts projected on the walls of the Art Museum chapel.)

But just when we thought Singapore art institutions had become truly gay-friendly, Fujiwara mailed me with this news: his work’s been censored. All the erotica’s been removed, rendering it, in his words, “meaningless, almost a tribute to Franco in the end”.

The museum staff didn’t even consult him or seek his permission to alter the piece – they simply altered it without his consent. What’s even more disturbing is that the changes were made only a week or two after the Biennale opened. Foreign arts journalists were thus given a view of a wonderfully liberal Singaporean arts scene, whereas us Singaporean viewers had that old, familiar conservative nanny-state treatment.

Mind you, like these organisers, I want Singapore to be a global centre for culture and the arts. Vandalising an award-winning artist’s work through censorship is not the way to make this happen. It sets a horrible precedent – what other international artist is going to be fool enough to show his work here after this?

Fujiwara is currently trying to arrange for his erotica to be replaced or his entire installation closed. Let’s hope the organisers come to their senses and restore the piece.

Fortunately, the Hotel Munber is an ongoing artwork, so it’ll be appearing intact in galleries across the world in the near future. There are plans for it to be shown later this year at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Tokyo: the first time his work will be shown in the country of his childhood. He’s also lined up for a retrospective in January next year at the Tate St. Ives, UK.

The following interview took place prior to the act of censorship. Fujiwara says he’d rather only be on record talking about his art, not how it was mutilated. (Apologies for the inconsistency.)

(And since I know some of you will ask: he’s taken. His boyfriend’s the Norwegian artist Ingar Dragset, also featured in the Biennale.)

æ: Age, Sex, Location?

Simon: 28, male, and I live in Berlin, Germany.

æ: Could you tell us a bit about your background?

Simon: I lived in Japan till it was four, so Japanese was my first language. Then I moved to England until I was 16, and then I quit high school and lived in Japan for a year and a half. I was working as a cello teacher and playing the cello in an Italian restaurant to make money. And I had my first boyfriend [there], so the first time I ever had sex was in Japan.

I’d given up on education: I wanted to work and be an adult. But I realised by the end of the year that I didn’t have enough skills and I didn’t know enough, so I went back to get more education. I went straight to a very strict all-boys’ boarding school in England, which is about the most opposite you could get to my life in Japan.

æ: I’ve heard some things about all-boys’ boarding schools, so I expect it wasn’t all boring.??

Simon: Well that would be telling. (laughs) I’ve got to have some secrets.

[After that] I went to Cambridge University and studied architecture. That gave me a lot of background in theory. But then I started to do art, because I felt somehow it was the freest area to explore ideas, without feeling constrained by building regulations or laws.

Simon Fujiwara

æ: Tell us about Welcome to The Hotel Munber.

Simon: It’s an unwritten erotic novel set in Franco’s Spain, which is a period in Spanish history when homosexuality was illegal and there was no published pornography or erotica because of the censorship of the dictator. My parents lived there at the end of that period.

My mum’s English and my dad’s Japanese, and they moved to Spain because they couldn’t live in each other’s countries. I grew up with all these stories about the hotel and this time of oppression, and I wanted to write a novel set in this period of oppression with a gay character.

Of course, using my parents’ stories, it was most easy to use my father as the main character. And of course this reflects on the idea that the dictatorship is like a patriarchy: that everyone who lives under the dictatorship somehow has to have a big daddy figure who rules over them and dictates what they should do. And that was connected to my relationship with my father: could I try to undermine that figure of a patriarchy by reflecting on the Franco dictatorship?

So I started to write the novel. But of course it was very difficult to do because of this idea of fusing your family history and eroticism.

æ: I watched your performance at the Singapore Art Museum, in which you describe how you turned your inability to complete the novel into an artwork. How have folks reacted to that?

Simon: It’s pretty open to people’s interpretations. A lot of straight men also say they find it very erotic listening to the stories, because they all happen in people’s imaginations. They’re mostly describing masturbatory fantasies, so they can be transferred to anyone. (laughs)

Some people react in a more academic way. They’re interested in the history of the period, and different forms of oppression through history, or they’re interested in how fiction and so-called reality are blended together, etc…

And then there’s the emotional tenor. Some read it as a completely personal work, and they say, “I haven’t spoken to my father for ten years and I couldn’t even think of having a relationship with him, but this is an example of how I could think about my family history, by retelling our stories or thinking about my own past.” So the reactions are completely varied.

æ: My friends have said they’re amazed such a sexually explicit artwork has been allowed here. Were there any problems bringing it in?

Simon: I had no problems. I mean, it was of course a concern before showing it, but there’s no way of knowing what will and what won’t be allowed.

I felt it’s important to show it here because of the situation I’ve heard from different friends and online about the kind of restrictive laws that are still in place in Singapore. And also this kind of pairing of this idea of the good life in Spain: you know, for British people Spain’s always been an exotic place [associated with] this idea of a sexual paradise, and Singapore could similarly be thought of in that way today, certainly in terms of its self-branding.

The Singapore government is trying to show this kind of relaxed state, very Western, very tropical, everything available. They seem to have slightly lax views on prostitution, which seems to be widely available. So it does have pragmatism about some forms of sexuality, knowing that travelers want to have sex when they come, so they allow certain things. But you never really know where that line is going to be drawn. As I understand, there’s a kind of strong religious movement here, a Christian movement, and of course this work is absolutely about undermining organised religion when it is fused with things like dictatorships.

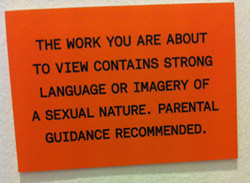

æ: But what about that sign (above) outside, warning people of the explicit content of your show?

Simon: It’s the first time that that’s ever happened when I’ve shown this work. But I like it as well: it raises the stakes in some kinds of ways. It gives people the false expectation that it’s going to be much more erotic than it is. And of course, everything happens in your mind in the installation, for example: you find two or three things which are obviously erotic, but then you have to find other things which are erotic.

This slapstick erotica is there in almost every single object, some kind of underlying fetish or sexual subversion of the nationalist tropes of Spain. The traditional baskets with dripping candle wax, wine barrels with fingers pointing out, castanets arranges like testicles – everything is arranged to make a sexual connotation. Really, with the installation, the way it functions is it puts the viewer in command of how much they can make sexual associations in their own minds. And it actually seems to work, even with old ladies.

æ: Your most iconic works, The Museum of Incest and The Hotel Munber, are both deeply rooted in exploring sexuality. Why do you think that’s the case?

Simon: Sexuality poses an unresolvable conflict. For me the idea was articulated best by Georges Bataille, [the surrealist writer]. He claims that sexuality is something that’s in conflict with civilization, because it’s about recreation (and sometimes procreation) but not necessarily about industry. And now of course we live in an age when everything is organized to suit the economy, a mega-industrialised age, and sexuality is being subsumed into that – but at the same time it needs to remain a kind of taboo to remain commercially viable.

Sex is something that can never be resolved. I mean, at the end of everything, will anyone ever be sexually satisfied? Even after you have sex, the next day, you want to have sex again. It’s a kind of continuously renewing force from within. And to work with an existing idea of the unresolvable keeps many doors open for the work. And formally with my work this is expressed through the unfinished nature of the projects, they all live in the proposal phase; the unwritten novel, the unfinished building…

I’m also curious about the fact that erotic art has not been particularly elevated in the hierarchy of art history; it’s always been a little frowned on. There are all these dreadful sex museums around the world, many of which I have visited out of curiosity or hope or something, and they are almost always tacky, stagey, semi-pornographic really places that are more about slapstick comedy: when you go to the gift shop you can buy mugs with penises on them. If that’s trying to deal with serious erotic issues then I don’t think it’s particularly successful.

The reason I work with gay material, apart from being personally interested in it, is that I have always felt a dissatisfaction with the way gay sexuality is represented in both mainstream heterosexual and gay media. On the one hand there’s a kind of superficial liberation of gay men’s sexualities, but as we all know from the mainstream gay press, it’s all about having one kind of body or one kind of sexual relationship.

With Welcome to The Hotel Munber, it’s hearkening back to a time before the Internet, before this so called liberation. The gay protagonist that is represented by my father lives in a dictatorship in an age before anyone’s online, and because he is alone in his world, his sexual life can only ever happen in his mind, which is definitely something that’s changed in society today.

One final point is that in the ‘90s and earlier, with gay artists there was a complete rejection of dealing with any kind of idea of family. I wanted to understand how the gay person fits back into the family, how you can never escape the fact that you come from a family and a society of reproductivity. With The Hotel Munber, it’s about me carrying on with my family history, not by having children but by telling [my family’s] stories, making them clearer, more political, righting the wrongs that my parents missed.

The Singapore Biennale runs from 13 March to 15 May 2011. Its venues are: the Singapore Art Museum, SAM at 8Q, Old Kallang Airport and Marina Bay. A $10 ticket is valid for admission to all sites. Simon’s work is installed in the Singapore Art Museum, 71 Bras Basah Road.

Ng Yi-Sheng is a poet and playwright, and winner of the Singapore Literature Prize in 2008 for his poetry anthology Last Boy.

Editor's note (Mar 26, 2011): Corrections were made to this article to reflect the artist's clarification that the Biennale curators were not involved in the act of censorship.