No American President probably looms as large in the political imagination as Abraham Lincoln. As commander-in-chief during his country’s greatest period of armed conflict up to that point in its history, as the Great Emancipator, and with an untimely death rendering him a martyr celebrated in poetry (‘O Captain! My Captain!’), Lincoln is in a morbid way, the forerunner to the cults of personality involving the Kennedy Brothers.

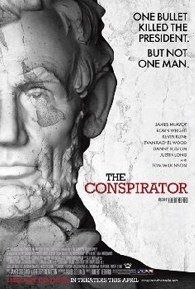

So it’s no surprise now that as American society finds itself in the need of some soul-searching, The Conspirator seems to have arrived as somewhat of an appetizer for Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln biopic to star Daniel Day Lewis. Set in the immediate period after the Lincoln Assassination, the film follows the trial of Mary Surratt (played by an unrecognisable Robin Wright), mother of John Surratt, one of the accused in the conspiracy to murder Lincoln. Mary supposedly owned the boarding house in Washington D.C. which was said to be the site where the conspiracy was planned.

Former Attorney-General Reverdy Johnson (Tom Wilkinson) appoints young lawyer Frederick Aiken (James McAvoy) to defend Mary Surratt, much to Aiken’s chagrin, given Aiken pretty much believes that Mary is most certainly a co-conspirator to her son’s crime. Aiken begins to face mounting obstacles, including his gradual ostracism from his usual favoured social circle, as a result of higher interference by the powers that be, led by vengeful Secretary of War Edwin Stanton (Kevin Kline), eager to punish the South.

It is easy to see the analogues today: with the Surratts as the 19th-Century equivalent of modern-day terror suspects, the Civil War as a national crisis on par with the war on terror, and the military trials vs civilian trials debate as an analogue for how the Guantanamo Bay terror suspects should be treated.

Redford, having openly said in interviews that it was an indirect attack on American policies involving the renditions of suspected terrorists and their inability to get a civilian trial, certainly goes out of his way to belabour the point to the extent that the film while well-made, stately and intelligent under Redford’s sure hand, is strikingly boring. The most intriguing story, in fact, goes out the window. The most interesting characters in the film are undoubtedly the Surratts, who juggle their multiple identities and loyalties as Southerners, Catholics, family and Americans, undoubtedly a similar dilemma to that which many terror suspects of American nationality face on a daily basis. Yet these characters are shoved aside to make way for drama between James McAvoy’s dashing but bland hero and Kevin Kline’s Machiavellian statesman, so openly plotting all he’s missing is a 19th-Century melodrama moustache to twirl.

The Conspirator is the first film from the American Film Company (AFC), which is apparently a new production company with a goal to make films that depict American history as accurately as possible. If this is a judge of things to come, the AFC could have a bright future in American filmmaking instead of being a niche studio for history buffs and Society of Creative Anachronism/Role-playing members, if only it but learns to tell stories instead of fables.

For a fable is sadly, at the end of the day what Robert Redford’s The Conspirator has turned out to be. The result is well-made liberal bait, but hardly the great story that it could have been.