Jon Chu's appropriation of action film narratology and aesthetics in his Step Up series is nothing short of forbidden alchemy, and it's successful. Just ask Channing Tatum, who had his acting career boosted into prime time with the first Step Up film, the dancers from So You Think You Can Dance who sign up for each new Step Up film to gain more celebrity sparkle even though Tatum was the only one who made it big time, and the audience who keep watching this series despite the ho-hum plots and the frankly forgettable though pleasant faces and bodies thrown their way.

But somewhere deep down inside, it's possible that the makers of the Step Up series realise there's only so far you can take the basic series template. Perhaps they fear that after a while, the audience might start rolling its collective eyeballs when a Step Up protagonist introduces himself and explains that his passion for dance is part of youthful rebellion and/or a search for self-identity and actualisation.

It's probably with that in mind that Step Up Revolution is well, sort of revolutionary. In beachfront Miami, a dance crew teams up with some street artists to put on flash mobs. They do it not because they are expressing themselves or they want to be heard; they're just a bunch of internet pranksters who do this because they want to win a YouTube contest where a cool million bucks are up for grabs. Like all flash mobs, their stunts are site-specific and cheeky, with just a slightest touch of jokey irony informing their dance/costumed flash mob routines. Like a heist film, the so creatively named Mob take over the streets, chi-chi restaurants, poseur-filled art galleries, even the city hall. They do their flash dance mob thing and flash out in well-positioned getaway trucks. That's refreshing given how jaded we are from the previous Step Up films where most dance routines happen indoors where dance is expected.

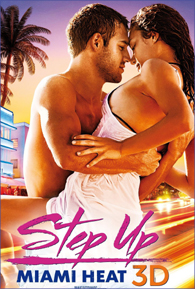

And since this is Miami we're talking about, the film even introduces some form of revolutionary struggle, though not with Castro. Peter Gallagher, who does not dance, is the hotel tycoon who wants to raze the public housing where most of the Mob's members live and play (they work in his hotel in the day). Given that his daughter, played by last season's So You Think You Can Dance finalist Kathryn McCormick, is a classical dancer who catches the eye of Mob leader (played by Ryan Guzman, a model who happens to know how to dance), the stage is set for the Mob taking on a more socially-conscious, class‑conscious protest against the fat cats of the city and capitalism in general.

The story that results is far less generic than you expect because Chu's team is politically sophisticated enough to realise and capitalise on the limitations of dance as a form of protest. That said, still the strongest point of this film is the impeccable choreography of the dance sequences and how new they seem to come across still this late in the series.