"People who do these things must be dead to all sense of shame, and one cannot hope to produce any effect upon them. It is the worst case I have tried... And that you, Wilde, have been the centre of a circle of extensive corruption of the most hideous kind among young men, it is equally impossible to doubt."

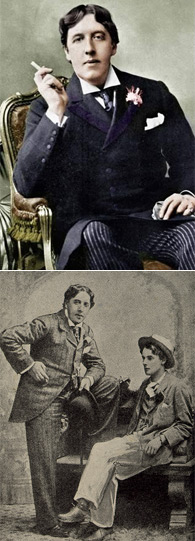

In 1895, Oscar Wilde was convicted of 'gross indecency' under a UK law that was the precursor of Singapore's infamous Section 377A. Bottom pic: Wilde (left) with his lover Lord Alfred Douglas (photo circa 1893) from whom the phrase "the Love that dare not speak its name" originated.

The law in this case was the Labouchere amendment of the Criminal Law Amendment Act, passed by the UK Parliament in 1885 that made a crime of "gross indecency." Singapore's Section 377A (Malaysia has a similar law) is descended from this law.

The case of Oscar Wilde was the most celebrated in the decade. It scandalised Britain, with rumours implicating a cabinet minister, and made him a household name through much of Europe and America, providing to this day a salutary lesson on the effects of anti-gay laws.

Wilde was already famous before the trials - there were three in quick succession. Since the late 1880s, he had become well known for his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray and his sell-out plays, such as Lady Windermere's Fan and The Importance of Being Earnest. Prior to that, he had been an art critic and had travelled around Britain and the US giving lectures on art and esthetics, albeit to no great success. Nor were his early plays, but eventually he found his voice, inventing single-handedly the form known as social comedy - plays filled with quick witty dialogue that poked fun at the manners, prejudices and hypocrisy of the upper classes.

He himself had displayed these verbal qualities for 20 years. One could always rely on him for a cutting repartee. It was a period when it was fashionable for men to be flamboyant, especially if one was involved in the theatre or the arts; Wilde's exaggerated personality stood out from his peers only by a matter of degree. However, he was also rather full of himself and could be disagreeably thoughtless, arrogant and stubborn.

Uranian tendencies

There is nothing to indicate that Wilde was aware of his "uranian tendencies" (in the language of the day) when he married Constance Lloyd in 1884. Wilde was 30, and the bride, 26, and they would have two sons soon after. He loved them deeply, but within three years of the marriage, the first homosexual affair had occurred, with 17-year-old Robert Ross who had moved into the Wilde family's house at Tite Street to stay three months while his single mother went abroad. He was preparing for his Cambridge entrance exam and might have been tutored by Wilde.

The biographer Barbara Belford noted that the same year, 1887, Wilde's most prolific period as a writer began, with the older man feeling at last "liberated, happy to be alive."

After Ross, Wilde began to explore London's underground homosexual scene. At first, Wilde relied on friends to introduce him to good-looking young men including one John Gray, a civil servant by day and a talented poet in his spare time. John Gray would inspire the character Dorian Gray in Wilde's 1889/1890 story of hedonism and eternal youth.

It would be another young man however, Lord Alfred Douglas, who would become the centre of Wilde's love-life. Nicknamed "Bosie," this very handsome 22-year-old was introduced to Wilde by a mutual friend in 1891, but it wasn't until the following year before the relationship got serious. Bosie was hardly an innocent boy; he had been sexually active during his schooldays and even during the time with Wilde, he was the more sexually outgoing of the two.

By this point, Wilde had become famous as a dramatist, and this might have got to his head, for he and Bosie made no effort to be discrete about their affair. Just about all their friends knew, though it is unlikely that Constance did, for Bosie was often welcomed to the Wildes' London townhouse or their vacation home in Torquay.

Within months, this affair had become a subject of blackmail. It happened when Bosie gave away one of his coats to an acquaintance, who found inside a pocket some letters from Wilde, one of which suggested a sexual relationship. Copies of this letter soon circulated and while Wilde bought the original back, he could not be so sure of the copies. In fact, one of them would later surface at his trials.

Despite outward appearances and undeniably deep emotional attachment, Wilde's relationship with Bosie was tumultuous. The younger man was willful and temperamental, sometimes returning Wilde's rather idealistic love with cruelty. In any case, they were sexually incompatible, both preferring young men. Intimacy between them petered out into a platonic friendship well before the trial and both had been largely looking to third parties for sex. Bosie, an advocate for sexual freedom, was the more reckless, leaving parties with beautiful young men in hand and even going to the East End, then a very low class area. Wilde preferred to have his rentboys discretely arranged by Bosie's friend, Alfred Taylor.

An irate father

Bosie's relationship with his father was strained, to say the least. The Marquess of Queensberry was a gruff and demanding man and when he found out about Bosie's relationship with Wilde, began to harass the latter to end it, often prowling the playwright's favourite restaurants looking for him. On one occasion, Queensberry intruded into Wilde's Tite Street home.

On 18 February 1895, Queensberry went to Wilde's club looking for him, but as he was not there, Queensberry left his name card with the porter, adding by hand the words, "To Oscar Wilde, posing as a somdomite [sic]". When Wilde saw this card on February 28, he decided that he had cause to make a police report against Queensberry for libel, since the older man had defamed him with those words to a third person - the porter.

And so it was Wilde who initiated the legal process, though understandably, he was sick of being harassed and persecuted by Queensberry, whose state of mind was now very unpredictable.

Queensberry's eldest son and Bosie's brother, Francis, Viscount Drumlanrig, had died the year before. Explained as a hunting accident, word circulated that it was actually a suicide and that Drumlanrig had had a romantic relationship with Lord Rosebery, the foreign minister (later Prime Minister. Having two sons the subject of scandalous gossip was perhaps too much for the man to bear. Around the same time, Queensberry's short-lived second marriage also came to an end - not by a divorce, but by an annulment on grounds that he was impotent.

Friends advised Wilde not to pursue the libel case against Queensberry since it might involve having to lie that he was a homosexual. But Wilde was determined to go ahead.

The trial opened on 3 April 1895 to a packed courtroom. Queensberry's barrister, Edward Carson, was well prepared, armed as he was with statements by a number of rentboys whom Wilde had been familiar with. Carson named three - Parker, Scarfe and Conway - in his opening statement. In the end, he didn't even have to produce them in court, for merely through cross-examination of Wilde himself, Carson was able to demonstrate that Wilde could have had no reason for meeting so often with these 18 to 20-year-olds other than sexual intimacy.

When the prosecution threw in the towel, abandoning the libel case, Wilde was left open to the charge of gross indecency as the statements that Carson had from the rentboys were deposited with the police and could be used against him. He was arrested the same day that his libel case collapsed.

Despite damaging evidence given by rentboys Fred Atkins, Charles Parker and William Parker and other witnesses, the second trial failed to produce a unanimous verdict from the jury, and so another one had to be convened.

The third trial began on 22 May with the same witnesses and letters in evidence but what was different about this trial was that the prosecution was led by none other than the Solicitor-General, Sir Frank Lockwood himself. It was quite extraordinary for such a senior representative of the Crown to take the lead, and in a case that didn't even involve murder or treason, and it suggested that the Crown was determined to obtain a conviction in order to make an example of Wilde. Why should that be? Word went around that Queensberry blackmailed Rosebery that he would reveal details of his affair with his son Drumlanrig if Wilde was not put away.

Wilde's most productive period was cut short by this turn of events; he never wrote a play again. His genius, however, outlived his persecutors, and the freedom to be true to our sexual selves, as he resolutely believed by the end of his life, is now seen as a moral right.

Tickets for the gala premiere are priced at $20 (US$15) and $50 (US$38) - the latter includes a cocktail reception - and are available online at www.fridae.asia/wilde.