Philippine Gay Culture: Binabae to Bakla, Silahis to MSM

By J. Neil C. Garcia

The 3rd Volume in the Queer Asia Series

Published by the Hong Kong University Press, 2009

The second reason for my conviction that I must approach this book with care is its complexity. It is a vast work of scholarship and argument, which, with its generous and detailed academic apparatus, reaches 536 pages in all, not something easily picked apart by a reviewer’s slight of hand in a thousand or so words. Then, for third, there is Garcia himself, a revered figure not only in the Philippine gay world but also in the literary, a poet, critic and writer who has a prominent place teaching creative writing and comparative literature at the University of the Philippines, Diliman. On top of this, he is one of the most pugnacious of writers, as a dip into any part of this book will prove, a writer of conviction and the power to express it, not a man, in short, with whom to trifle! And finally, and this is a confession on my part, the fourth reason for more than the usual circumspection here is that I am no student of, let alone expert in, the Philippine gay scene; I am in no position to compare and contrast, and, as most of the book’s new readers will, must be content to place myself in Garcia’s hands for the history and theory that he unfolds.

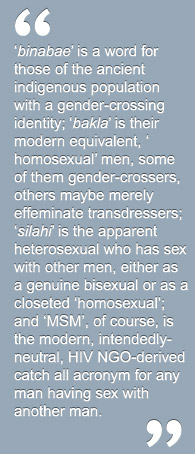

So, foreign perspectives don’t work when applied here, and Garcia’s exhaustive investigation into his country’s gay culture takes him down some unexpected paths. He traces the modern bakla back to the tribes inhabiting the archipelago before the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th Century. These conquerors suppressed, perverted and misrepresented the culture of the people they colonised and converted to Christianity. Back then, binabae, priests (local shamans) played key roles in their people’s spiritual lives, and these binabae could be female or male-to-female transgendered. Philippine culture conceived of the person as having an interior (loob) separate from, and with greater value than, their exterior (labas). So transgendered persons were accepted as those fulfilling their loob in their labas. Christian suppression of both native religious beliefs and sexual practices submerged this system, but enough of it remained to evolve into the local culture of the bakla, effeminate men (many of them transgendered) who dress as women, behave and often work as women, and who are 'used' by men as women. Whilst their modern typical occupations of hairdresser, window dresser, beautician, and the like, echo the katoey and similar manifestations, they differ in that the bakla are not prostitutes, and, in fact, if they find relationships with men, inevitably end up paying for the upkeep of their ‘spouses’. The men, of course, remain dominant and heterosexual (in their own eyes) in these relationships. When the western sexologists’ discourse of inversion (of homosexuals being women in men’s bodies) arrived in the Philippines, it elided into the local culture of loob, and similarly, later, the words ‘homosexual’ and ‘gay’ attached to the bakla.

In Part One, Garcia investigates these systems and looks at the indigenous pre-colonial culture still (partially) visible from colonial records, then, in the order of his chronological survey (which is not that of his book), jumps to the four decades from the Sixties to the Nineties, examining each in turn and using them to develop and illustrate his theme. Part Two of the book is very different, a study of three Philippine writers, Severino Montano, Orlando Nadres and Tony Perez, whose works Garcia examines in the light of his research and theories and whose sexual politics he criticises. He has chosen these three writers (for reasons not entirely clear in the text) to make what he describes as ‘the first […] project in local literary criticism with homosexual writings as the specific object of scrutiny.’

The Lion and the Faun, Montano’s huge unpublished novel (Garcia had seen only its first half of five hundred pages when he wrote this book) was written many years before and covers the 1950s and 1960s, something, perhaps, of a Philippine equivalent to EM Forster’s Maurice. Garcia dislikes this story of closeted gay (non bakla) love, with its misogynist and macho themes, and attacks it accordingly, taking the unusual stance, as he does in all his criticism in this book, that only a gay man can write a convincingly authentic gay novel, which has, therefore, to be a sort of roman a clef. With playwright Orlando Nadres, author of a frequently performed and very popular Tagalog play (in its English translation named That’s All for Now and Many Thanks), Garcia is back on the more favoured ground of the bakla, one of whom is much featured in the play. The third work examined here, Tony Perez’s novella Cubao 1980, a tale of two male prostitutes, is not, to Garcia’s way of looking at gay culture, about the gay world or its liberation at all (for many reasons, one being that it misses the ‘pain’ of the bakla’s condition entirely). It gets as short a shrift here as does The Lion and the Faun.

Part Two of Garcia’s book is eccentric, not, as the first section was a review of gay culture through history, a parallel review of Philippine gay literature over time, but rather a dissection of three works using the theoretical tools he develops in Part One of the book. This makes Philippine Gay Culture a train of two carriages hitched together by an interconnecting internal argument. Yet none of this detracts from the writing of the second part, where Garcia romps around on his home ground of literary criticism. His writing in Part Two is clearly the better of the two. Garcia does not fail to amuse here; he is lively, cheeky, cutting, bruising and never dull. His insights into the works he examines are the results, in part, of the test tube experiments he conducts into the literature using the tools of the theories he has developed in Part One.

Don’t read this book expecting an easy ride. Garcia is very persuasive (watch his arguments carefully before you get carried away by his conviction!) and has huge knowledge which he wields with much common sense. After a good deal of the required reflection, there is not much for a general reader to find to quarrel with in the conclusions which he reaches. The information and arguments deployed, however, to reach those conclusions, can be, at times, maddeningly convoluted, dense and repetitive, and the book would benefit from both reorganising and pruning. He has the grace to admit this himself in the ‘Author’s Note’: ‘I am no longer the clumsily prolix, overeager, wide-eyed and theory-crazed person who cobbled together these words’. That said, he left the book as it was in the second and third editions with ‘only a modicum of blue-pencilling and emendation.’

That he is unapologetically an advocate for bakla culture (kabaklaan) may or may not be a defect in the thrust of the book; I possess no alternative sources to reveal any special pleading. It would have been interesting, though, had the later editions followed through his arguments to examine more closely the evolution of gay culture in the Philippines from the '90s till today. There remains, I think, a need to prove or disprove the continuing centrality of kabaklaan to gay culture there. Has MSM started the process of the development of more westernised styles of a more equal male-male love? We are left unsure. Garcia cites the recent coming out in public of at least one prominent man of upper class, but this is not enough to evince a trend and it would be interesting to see if yet another post-colonial foreign imposition is now changing the way the Philippine gay world sees itself in the new millennium.

Should you buy this book? Most certainly. This is a thorough and deeply considered study of a unique culture which elucidates some very surprising (to foreigners) phenomena and comes to unusual conclusions which have both utility for an understanding of the Philippines and stand as convincing testimony that queer theory as an academic discourse must account for a myriad of queer theories if it is to describe the world we live in. More than this, Philippine Gay Culture is a brave polemic, a call to freedom, by a fine writer and a decent man. Buy it, stick with it, bite off small bits of it at a time if you have to, but read this book!