But a different interpretation of Haneke is generally advanced by me, when I say that while Haneke’s reputation for cruel psychological dramas is not undeserved, he is a far slier and subtler filmmaker than given credit for, and most of his films come with a kind of demonic hidden laugh track built into their respective universes. Funny Games , while promoted as a condemnation of the Scream and Saw franchises and their ilk in trivializing human death, is equally an absurdist masterpiece in which bourgeois manners, expectations and perceptions are systematically mocked in a manner not unlike Bunuel at his finest.

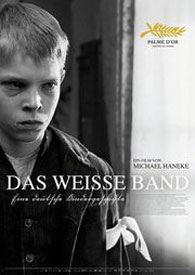

Once again, The White Ribbon is a showcase of Haneke’s unique brand of sly deceptiveness. The setting is a German village called Eichwald at the turn of the century. A sleepy, well-ordered place in which nearly everyone is labeled by their vocation, including the story’s narrator, a School Teacher. Befitting the illiberal and authoritarian nature of much European society at the time, it is a general rule that women and children should be seen and not heard, and generally disciplined to keep in line with the men. The treatment of both tended towards the cruel. Over a year, just before the Great War, a series of accidents happen in the village in which the doctor has his horse tripped, children go missing and are found horribly hurt and mutilated, barns burn down and accidents kill innocents, among others.

In The White Ribbon, with the subtitle “A German Children’s Story”, the unreliable narrator and common historical knowledge have subtly convinced most reviewers and audiences that it is a foreshadow about the rise of Nazism. Not the least aided by the imagery conveyed by the titular white ribbons, placed by the town’s pastor on his children to remind them of innocence and purity, which Haneke chooses to cleverly place in the same positions as Nazi armbands. The same pastor’s disproportionate punishments for his children’s minor transgressions and his overall loveless treatment of them also echo works by Alice Miller that draw parallels between abusive child-rearing methods and sociopathic, authoritarian thought-patterns. However, the deceptiveness of Haneke is that all this is just a red herring in terms of genre. The most effective way to see The White Ribbon is as a portrayal of what happens to a well-ordered community when faced with unknowable misfortune, and its ensuing unraveling in the face of its well-guarded taboos. Above either being a mystery or a horror it is a first-rate, astute psychological drama that examines the unspoken taboos that hold a community together and that keep a way of life together, while also aiding as the dressing that covers up the numerous skeletons in the closet that plague the community. Over the course of two hours, we are introduced to a community and get to know its characters intimately, far more than we ever do in terms of learning about the series of crimes and who committed them. In this case, The White Ribbon calls to mind another famous Korean “thriller”, Bong Jun Ho’s Memories of Murder, which was a comical examination of institutional corruption, brutality and ineffectiveness in 1980s South Korea under the guise of a crime thriller.

The one downside is really Christian Berger’s mock-Ingmar Bergman cinematography, which comes off too smooth and crisp to achieve the mood. The film was apparently shot on 35 mm and had post production done in Digital, which likely accounts for this oddly unsatisfying visual feel. Still, The White Ribbon succeeds brilliantly as a deceptively deep drama in the guise of a mystery thriller, in which Michael Haneke once again among the most sly of filmmakers working today.