Coming in the post-Michael Moore era of documentary filmmaking, Morgan Spurlock may be the best living documentarian yet. As Spurlock has proven with his break-out Super Size Me, there is still a place in this world for documentaries that entertain and educate without being adversarial, hectoring, and shrill. In a world where more and more issues are becoming polarised, that’s an achievement.

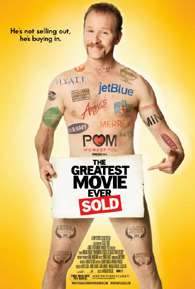

In The Greatest Movie Ever Sold, Spurlock takes on the polarising issue of product placement and stealth advertising in film and television with grace, humour, sincerity, and a willingness to be non-partisan. The premise of the documentary and the cornerstone that makes it so cleverly entertaining – Spurlock learns about product placement by setting out making a film that is 100% funded by product placements and this is the same film that you are watching in the cinema.

Of course, there is the prerequisite show-and-tell segment of just how insidious product placement has become in popular entertainment, just to show less media-savvy audiences how much they’re being advertised to. And a few interviews with the standard academic talking heads and consumer group advocates, as well as artists whose work would never have been made without paid sponsorship. It’s all very educational, of course.

But what makes The Greatest Movie Ever Sold such a cheeky, post-modern and, as an advertising executive in the film calls it, “pleasingly circular”, is watching Morgan Spurlock pitch this documentary idea to receptive corporations, negotiate terms with them, making the most extravagant promises to get their sponsorship, and then see each promise fulfilled while generating laughs, exposing the inner workings of media advertising, while never compromising the integrity of his project.

Is Spurlock a sell-out then? Not by any means. The puckish filmmaker insists on total transparency, documenting in fascinating detail the entire process for us – and demystifies the phenomenon of advertising. By surrendering himself to that process, Spurlock surrenders himself to the possibility of having his cake and eating it too.