First the bad news. We are not named. In the anti-discrimination provisions there is no reference to “sexual orientation” or “gender identity” or “gender expression.” Perhaps we don’t exist.

Secondly, marriage involves “men and women,” which sounds like it does not include two men or two women.

The wording of the draft is copied directly from the UN’s two most important human rights documents, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), passed by the General Assembly in 1948, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) of 1966, a human rights treaty that must be signed by individual states to be binding on them.

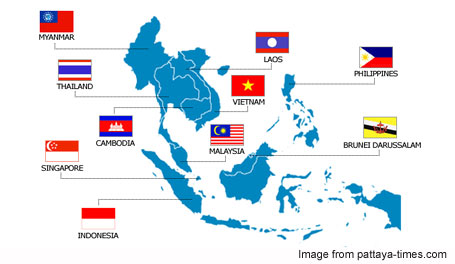

The real master text is the UDHR. The ICCPR could only copy. In the same way the drafters of the ASEAN Human Rights Declaration (ADHR) are only able to copy (given the politics of the moment).

The ICCPR has been signed by Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam, six of the 10 members of ASEAN. For them, the ASEAN draft declaration simply repeats what they have already agreed to. For the others (Brunei, Malaysia, Myanmar and Singapore) it can be seen as a step forward.

Singapore, which has prided itself on being the sophisticated skeptic on human rights, will now be indirectly signing the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights when it approves the draft ASEAN declaration. It will be supporting the wording that led the UN to declare that sodomy laws violate international human rights principles. What will the government lawyers say in court when the judges hear the case challenging Singapore’s Article 377A?

Equality / non-discrimination

At present no ASEAN member country has a general anti-discrimination law prohibiting discrimination by governments and private businesses on grounds such as those listed in the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. The only jurisdiction in Asia which says you cannot be fired from your job just because you are gay is Taiwan.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights both condemn discrimination “of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.”

There are three important parts to this provision: (1) a general rejection of discrimination “of any kind”, (2) examples of prohibited grounds of discrimination, such as race and sex, and (3) an added catch-all category – “or other status” – to make sure that the section is not restrictively interpreted. We are included, but we are not named.

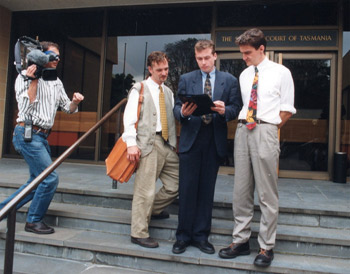

Nicholas Toonen discussing the UN case in the media glare with

Rodney Croome (right) and legal advisor Wayne Morgan (left).

UN Human Rights Commissioner, Navi Pillay, says the UN's decision

in 1994 to uphold Nick Toonen's case and condemn Tasmania's

former anti-gay laws "reverberated around the world" because it was

the first time the UN acknowledged that the right to be free from

discrimination applies to everyone regardless of sexual orientation.

Photo: tidningenkomut.se

When the sodomy law in the Australian State of Tasmania was challenged by the gay activist Nicholas Toonen, the Australian government (which wanted to lose the case), asked the UN Human Rights Committee (which supervises compliance with the ICCPR) to answer whether “sexual orientation” was included within the phrase “other status.”

To the surprise of many the Committee (composed of independent experts) avoided that request and ruled that discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation was part of discrimination on the basis of sex.

Wow! What a gift! They were saying that any constitution or law or treaty provision which condemned discrimination on the basis of sex – and there are lots of such provisions – condemned not only discrimination against women, but discrimination against gays, lesbians and bisexuals as well.

Ever since the decision in Toonen v Australia in 1994 the Human Rights Committee has been telling countries that have signed the ICCPR that they should end any criminal prohibitions. Since the beginning of the new Universal Periodic Review process, ad hoc committees of the UN Human Rights Council have been telling all countries to end criminal prohibitions.

Even Brunei probably has laws saying there should be no discrimination on the basis of sex. They still have a colonial-era criminal prohibition. Its days are numbered.

Marriage

Both the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the ICCPR uphold the rights of men and women of full age to marry and found a family. The family is described as a fundamental unit of society, and governments are invited to give it protection.

New Zealand recognised equal rights for same-sex couples with a registration system, but withheld the name “marriage.” In two cases on pensions (one involving Australia and the other Colombia), the Human Rights Committee ruled that same-sex couples had to be treated in the same way as heterosexual couples. Our relationships were being given equal recognition.

In 2002 in the case of Joslin v New Zealand, the Human Rights Committee ruled that New Zealand could withhold the ‘marriage’ title. There should be no discrimination in terms of substantive rights, but the official name used did not have to be the same. 2002 was a very early time for a marriage case to go to the Human Rights Committee. The first country to open marriage had been the Netherlands in 2001. The case was premature.

Damage was limited in two ways. It was made clear that the reason for rejecting marriage was the precise wording of the ICCPR. The marriage section is the only part of the document that uses gendered language – referring specifically to “men and women…”

The ICCPR had a specific, conventional attitude towards “marriage”. The denial of marriage might offend the non-discrimination clause, but that broad provision was limited by the specific language of the section on “marriage”. No other right or benefit has been denied by the committee on the basis of the gendered wording of the marriage section.

The Joslin decision was a loss – but the narrowest possible loss. We lost the name. We did not lose in any other way the right to equality.

Look at the Yogyakarta Principles. They are newer, but still before the big swell on extending marriage. They call for equal rights and benefits for same-sex couples, but do not call for the equal use of the term “marriage.” The Yogyakarta Principles would have been vulnerable to attack if they had ignored the Joslin ruling.

Someday Joslin will be reversed, but not for a while. Meanwhile we are winning on the ‘marriage’ issue day by day.

For us the ASEAN draft declaration on human rights is not a step backward. In fact it pushes the four countries (Brunei, Malaysia, Myanmar and Singapore) a bit closer to the realities of the 21st century.

Doug Sanders is a retired Canadian law professor, living in Bangkok. He can be contacted at sanders_gwb@yahoo.ca.