While some people still hold the outdated view that homosexuality is a Western import into Asia, it cannot be further from the truth. For centuries, cultural depictions of same-sex relations have existed in art, literature and folklore across the world’s most populous continent.

From the classic ancient Hindu text Kama Sutra, to the well-documented history of romantic and sexual relationships between men across various Chinese dynasties; from the celebrated same-sex love between Japanese monks and samurais, to the Thai tradition of recognising the kathoey as a third gender. For the longest time, homosexuality has always been an integral part of Asian civilisations. It is only in recent centuries, with European colonial expansion and subsequent legislations, that homophobia and homophobic attitudes have become the norm in Asia.

Homophobia refers to one’s feelings of fear, hatred or disgust towards homosexuals, and the prejudiced view that gay men and lesbians are wrong, immoral, sick or sinful.

Here is a real-life example of homophobic bullying through name-calling:

‘I was walking out of the school one day towards the bus stop, when this guy screamed at me, “Hey faggot!”’

Homophobia can, and does, exist in every aspect of our lives. If you’re a gay man and someone asks you and your boyfriend the question, “Who is the ‘man’ and who is the ‘woman’ in your relationship?” That is homophobia. It shows that the person asking is ignorant, and the question itself is offensive in nature.

In a survey conducted in 2012 in Singapore by Oogachaga, a gay-affirmative counselling and personal development agency, 60.2% of the respondents indicated they have had experiences with sexual orientation and/or gender identity based abuse and discrimination. Gay males (62.5%) experienced the second highest incidence of such experiences after transgender females.

Yet ironically, it is not only non-gay people who are guilty of spreading homophobia. Most gay men in Asia grow up and live in homophobic, heteronormative environments, where the prevailing norm is to be heterosexual, be interested in the opposite sex, marry and have children. It is therefore not unusual for many of us to internalise this homophobia, and express it in our daily lives.

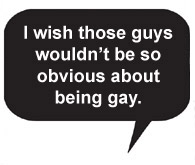

Internalised homophobia can take the form of a gay individual’s attitudes, language or behaviours. Examples of a gay man internalising homophobia include: being uncomfortable with public displays of affection between two men, but accepting of a man kissing a woman on the street; calling effeminate men insulting terms like “fag” or “sissy”, but not allowing others to use those terms on yourself; assuming that all gay men are sexually promiscuous and unfaithful; or making comments like, “I wish those guys wouldn’t be so obvious about being gay.”

It requires a high level of self-awareness to check our own internalised homophobia. And it means asking ourselves some difficult questions:

“Do I identify myself as gay, queer, bisexual or closeted? Or do I just have dates or sex with other guys, but I’m not ‘openly’ gay?”

“Am I comfortable with how I see myself? Or with how other people see me?”

“How comfortable am I to see other gay, queer, bisexual or closeted men? How do I feel about how I see and respond to them?”

“How do I think I might see myself differently in a few years’ time?”

These self-reflective questions are very personal in nature, and there are no right or wrong answers. But one thing for sure: Homophobia is rendered obsolete when we recognise it in ourselves, or when we call it out for what it is in other people.

Homophobic people become powerless when we identify them for who they are and what they represent. We can challenge their homophobic views as unacceptable, with reason and logic. We can dispel their fear-mongering with our personal life experiences. And we can end homophobia when we fight for equality before the law.

Leow Yangfa is the editor of I Will Survive: Personal gay, lesbian, bisexual & transgender stories in Singapore. He is also deputy executive director of Oogachaga, an LGBT-affirming counselling and development agency in Singapore.

This article is originally published in Element magazine Vol.3. To purchase Element magazine, log onto www.elementmag.asia for more information.