My first boyfriend died of AIDS about two years after we broke up. I found out about it more than a year after his death, of all times and places, during the 1st Singapore AIDS conference in 1998, when a mutual friend, a Taiwanese representative to the conference, asked me out to lunch, and dropped the bomb shell.

Immediately after that, a wave of sadness came over me. Naturally I was sad because someone I knew and was close to had died. But underneath that was an even deeper sadness. It was hard to articulate why I was so sad, but it was very clear what the sadness did. It made me totally incapable of being angry with him. My boyfriend at that time was livid. He thought it was utterly irresponsible for my ex to hide his HIV status from me. I could have been infected.

He was right. But all I wanted to do, was to gather all the photographs I had of him, put them into an album, and look at them anew, wondering what he was thinking and feeling at those times, smiling into the camera with me by his side, and knowing his days were numbered.

Why didn't he tell me the truth about his HIV status? He was a medical doctor. He kept telling all our mutual gay friends to get tested. He taught me all about safe sex when I first came out. So why couldn't he tell me he was positive?

I will never know the answer. But I can guess. Would I have entered into a relationship with him if I had known this when we first met? To be perfectly honest, no. Hell no! AIDS to me then, in the early 90s was something that happened in San Francisco. It was something remote. That did not mean I didn't take precautions, but it did mean I never thought it possible that someone I knew could be HIV+. If he had told me, I would probably have freaked out. And I guess he knew that too.

Perhaps you can now understand why I was so sad. The stigma of HIV was so great that he could not even share it with someone he loved. What was it like for him, to keep this secret in order to have some semblance of normality in his life? And I, together with the Taiwanese society at that time, contributed to his need for secrecy.

It was very difficult to come to grips with this: I was stunned to realise years later that I was stigmatising my own boyfriend.

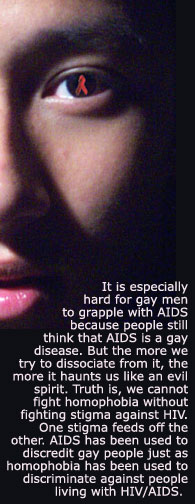

It is especially hard for gay men to grapple with AIDS because people still think that AIDS is a gay disease. But the more we try to dissociate from it, the more it haunts us like an evil spirit. Truth is, we cannot fight homophobia without fighting stigma against HIV. One stigma feeds off the other. AIDS has been used to discredit gay people just as homophobia has been used to discriminate against people living with HIV/AIDS.

And stigmas, like taboos, are often hidden. Imagine a society who in reality is homophobic but will not admit it, preferring to think of itself as morally superior instead. They will say no, we talk about the gays openly, we are not anti-gay, just don't hold hands in front of the kids. But we, on the receiving end, can all decipher the don't-come-too-close-to-me grammar of "the gays" and the convenience of hiding behind "the kids."

We are just as guilty when it comes to folks who are HIV+. We know they exist, we talk about HIV every so often, but we would rather not have them come too close. How do you think our fellow gay HIV+ men feel when they decipher our hidden stigmatisation towards them?

I remember a moment in a play that The Necessary Stage did with Paddy Chew, the only person in Singapore who has ever come out as HIV+. During the Question and Answer segment in the middle of the play, a member of the audience asked: "help me understand you, what can I do to help?" That was a magical moment. It was a moment when Paddy the actor on stage stopped being the emasculated symbol of AIDS, a promiscuous gay man, an object for observation, but became a person with feelings and needs, foibles and strengths, deserving of respect, understanding and compassion - just like everyone else.

Stigmatisation runs the full gamut from very subtle to rabidly hysterical. For hysterical, try rabidly anti-gay televangelist Jerry Falwell: "AIDS is not just God's punishment for homosexuals; it is God's punishment for the society that tolerates homosexuals." For subtle stigmatisation, what I did was a good example. At its core, stigmatisation is selfish indifference to human suffering: it's your own fault, so stay away from me. Contrast that to: help me understand, what can I do to help?

As sexual minorities, we are well acquainted with stigmatisation. Let's not do it to others. Few of us are hysterical, but many of us stigmatise PLWHA so subtly that we are not even aware of it ourselves. We can do better.

John Manzon-Santos, Executive Director of the San Francisco-based Asian & Pacific Islander Wellness Center, gave me this idea and I would like to share it with you. If you already know someone who is HIV+, come out about him/her to your friends and family. Tell them about your HIV+ friend and help them see your friend as a person. From you, they will learn compassion and understanding rather than recoil as a way to relate to people who are HIV+. If you don't know anyone who is positive, go and volunteer at your local HIV/AIDS organisation and soon, you too will have a HIV+ friend. If you feel coming out as gay or lesbian was hard, imagine how much harder it is to come out as HIV+. There is no need to wait for another Paddy Chew, or for the government to change its mind. How much longer do you want your friends to be living under such a heavy stigma? Do something about it today.

Dr Tan Chong Kee holds a Ph.D. in Chinese Literature from Stanford University in the United States and is one of Singapore's best-known figures in civil society activism.