Stigmas surrounding HIV/AIDS have always been prevalent in Singapore since the disease was first reported in the media (John 1997) and researchers have found that accurate knowledge about HIV and its transmission alone has not reduced the stigma associated with People Living With HIV and AIDS (Lim, Teo, Teo & Tan 1999) or PLWHA for short. Although there had been earlier de-stigmatising efforts initiated by far-sighted civil society groups such as Action for AIDS and The Necessary Stage (1), to date, there have not been any concerted national program to address this issue. Recent public pronouncements and actions by the Ministry of Health have further reinforced existing stigmas. The situation is further compounded by what appears to be official refusal to admit that stigmas such as anti-gay attitudes (homophobia) are an integral piece of the HIV puzzle in Singapore (2).

This essay makes three main arguments. One, that stigmatisation is not an Asian cultural value, but a degrading process that exacts huge social costs. Two, that destigmatisation campaigns, which are so far non-existent in Singapore, is a vital and pivotal piece of the puzzle for effective HIV prevention because stigma can greatly compromise the effectiveness of any HIV prevention work. Three, that there already exist many successful case studies from all parts of the world where empowered civil society groups succeed in fighting the spread of the HIV virus. Many of these either have a destigmatisation component or can assume an environment where stigma is not so debilitating. Singapore can benefit greatly by learning from them.

What is the relationship between Stigmas and Morality?

E. Goffman in Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoilt Identity defines stigma as something that reduces the person "from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one" (Goffman 1963). The original meaning of this word refers to marks made on the body (usually burnt or cut) to signify that the person is a slave, criminal, traitor, or of flawed moral status, to be avoided in public. Social stigma is thus a "mark of infamy or disgrace; sign of moral blemish; stain or reproach caused by dishonourable conduct (Wikipedia)."

The related notion of stigmatisation, according to an UNAIDS document, is an arbitrary process where "certain characteristics are seized upon and defined by others as discreditable or unworthy… [it is] a process of devaluation." (Aggleton & Parker 2002). This process of devaluation takes many forms. Some common ones are denial of equal access to treatment, voyeurism and sensationalism, public castigation, etc. Thus, Stigma as a mark of disgrace attached by one group on to another and stigmatisation as a process of devaluation are very closely tied to each other. One motivates the other: because you are so disgraced, it is right that you are discriminated against.

When asked about various government policies that discriminate against PLWHA, the standard response has been that Singapore is a conservative society with Asian values. The implication seems to be that "conservative Asian societies" should be left to discriminate in peace even if their own citizens object to it. The fact is that HIV-related stigmas exist in almost all countries regardless of whether they are Asian, Western, African, South American, etc. These different countries have also tried to justify the stigmas in similar ways: by claiming that it is an integral part of their culture. There is nothing intrinsically Asian, Western, African or Latino about these stigmas. They are so universal because they originate from universal human conditions of fear towards something different. However, because the attitude born out of the fear of others is so strong, it is misrecognised as intrinsic and then justified by claiming that it is motivated by intrinsic cultural values. In the West, Christianity is often used as the justification. In Singapore, it is Confucianism (or its later incarnation as 'Asian Values'). It is particularly interesting in Singapore's case because "Asian" and "Christian" and "Western" are all labels that collapse under examination: If we look behind the "Asian" label, the most vocal supporters of these stigmas are often Christian groups, some of them affiliated with their parent group in the United States.

As the devastation of this disease multiplied, infecting people of all age groups, races, sexualities, genders, socio-economic status, etc., more and countries are now abandoning stigmatisation and discrimination in favour of a more pragmatic and rational public health approach to stem the spread of the virus. A significant example for Singapore is that China, the original Confucian nation, has now embraced the importance of de-stigmatisation and the need to provide universal access to treatment (Paulo 14 September 2005, China AIDS Survey). Unless we want to claim that China is no longer Confucian and "Asian values" are no longer relevant there, we have to grant that it is possible for Asian nations to retain their cultural values while de-stigmatising HIV/AIDS and providing affordable treatment to all PLWHAs.

A common attitude towards HIV in Singapore is that people who are HIV positive brought it upon themselves. What people forget is that the same can be said for many other diseases. Heart patients can be said to have "brought it upon themselves" for smoking, not watching their diet and/or not exercising regularly. Similarly, short-sighted people "brought it upon themselves" for having bad reading habits. People with back pain "brought it upon themselves" for having bad postures. And the list goes on and on. We all know it is meaningless to heap on blame in these cases. It is much more useful to treat their conditions and help them develop better habits. Unfortunately, the fear and stigmas surrounding HIV have made it less obvious that blaming HIV+ patients is equally unhelpful, and that the way forward is also to treat their conditions and help them develop better habits.

The crux of the moral issue surround HIV/AIDS is this: what is the moral response to HIV/AIDS? Is it to cast stones from a safe distance of "it can't happen to me"? Or is it to intervene with compassion to reduce its spread? No one will openly say it is to cast stones. What we need to be vigilant against, however, are stone-casting responses disguised as helping hands. The way to distinguish between a moral and an immoral response is very simple. We should ask: is the response truly aimed at reducing the spread of HIV, or is it about upholding certain notions of "moral standards" while having detrimental effects on HIV prevention, in reality.

What stigmas are associated with HIV/AIDS?

Before we can design a de-stigmatisation campaign, we need to first understand the nature of stigma. There are several powerful stigmas operating with respect to HIV/AIDS in Singapore. Most of these stigmas are very similar to those operating in other countries while one of them is usually only found in authoritarian ones. Without any claim of being exhaustive, I shall briefly illustrate some of them.

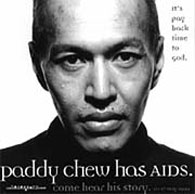

There is still widespread fear and unease among Singaporeans towards People Living With HIV/AIDS (PLWHA). HIV/AIDS is still perceived as a fatal disease even though medical advances have made it more akin to a chronic disease. There is so far no distinction in public education message between the seriousness of the virus on the one hand and compassion for PLWHA on the other. Thus, fear of the virus has become conflated with fear of PLWHA. Added to this is the common moral judgment that HIV+ adults got the virus through their own fault. The combined stigma of disease, death and moral defectiveness is a very potent and loaded sign that marks PLWHAs as complete social outcasts. Because this particular combination of stigma is so debilitating, so far, there has only been one exceptional individual (Paddy Chew) who admitted to being HIV+, and after his death, no one else has been willing to do so.

Homophobia

In Singapore, especially recently, government officials and the mass media have spread the impression that HIV is a gay disease (Arshad 14 March 2005, Ng 13 March 2005). This is particularly telling as an indicator of homophobia since the vast majority of Singaporeans with HIV, about 75%, are, in fact, heterosexuals.

The effect of strongly linking public perception of HIV/AIDS with homosexuality is that the homophobic stigma becomes attached to the stigma of HIV/AIDS (3).

The controversy created by then Minister of State for health, Dr Balaji Sadasivan, when he blamed gay Singaporeans for causing a rise in HIV infection rate (Ng 13 March 2005, Arshad 14 March 2005) is an illustration of how widespread homophobia is in Singapore society, and how easy it is to blame gay men for a disease that cuts across all social categorisations (4). Whether or not attendance at gay parties is correlated to HIV infection is a simple fact. A fact cannot be homophobic. What is homophobic is how that fact is used. It can be used to inform HIV prevention efforts and the production of outreach materials addressing the specific needs of party-going gay men to promote safe sex, or it can be used to cast a negative light on gay men and arouse public abhorrence against them. Dr Sadasivan's public statement had aroused great public consternation about homosexuality and HIV, to the point where people are prepared to target and infringe on the individual rights of gay men (5).

HIV infection statistics for 2005 shows a substantial rise of new infections among the Malay population in Singapore from 8.1% of total infections from 1985 - 2004 to 13.3% in 2005 (MOH website 2006). This is particularly worrisome as the percentage of infection among all other ethnic groups is either stabilising or declining. No government official has publicly blamed the Malay community for their high infection rate. To do so will be considered racist and rightly so. One hopes, however, that MOH is taking notice of this trend and doing something about it (6).

Sexism

Patriarchal prejudice casts women as the weaker sex needing the state's protection. They are not seen as empowered individuals fully capable of protecting themselves. This prejudice is very subtle because on the surface, it appears to give women an unfair advantage before the law for things like rape, child custody, alimony, etc. However, what it does is to relegate women to the social role of the passive disempowered victim. Tellingly, the health junior minister expanded considerable effort to start public discussions about a law to punish husbands who pass HIV to their wives (Ramani 1 December 2005), but did not expend any effort to initiate public discussion about how to empower married women to negotiate safe sex with their straying husbands or to educate women about the female condom. The patriarchal Singapore state seems to feel that men are responsible for their wives' sexual health while women are simply expected to stay faithful to their husbands. Although common sense tells us that taking responsibility for one's own prevention through self-empowerment is better than hoping others will take responsibility through fear of punishment, the power of sexism has led even some women to strongly support punishment instead (Arshad 25 March 2005).

Sex Phobia

The Singapore state diligently censors sex from movies while letting through extreme violence. This same attitude extends to HIV prevention. Police banned the distribution of safe sex brochures at Fridae's Nation party and Dr Sadasivan justified the ban by saying, "Handing out pornography is not the solution to the spread of Aids" (Sadasivan 29 March 2005). Notice that whether or not these 'pornographic' outreach materials were effective in promoting safe sex was not a consideration, but how they might infringe on certain notions of 'moral standard' was. This 'moral standard' is in fact sex phobia.

Experience from many other countries have taught us that one major reason for men not using condom during sex is that they feel it is not sexy. If men feel they have to choose between having good OR safe sex, safe sex rate will suffer. Thus, one very important and practical message in HIV prevention education is to create the feeling that condom can be sexy, that safe sex can be good sex. Instead, in Singapore, we now have a curious requirement that sex must not figure in public education material to promote safe sex.

More damaging than sub-optimal outreach material, sex phobia is probably also motivating the Health Ministry to block a wider promotion of condom use in favour of the "Abstinence" and/or "Be Faithful" message. Instead of scientifically studying the population to determine which message is most effective for which segment, it is making such decisions by decree based on what it calls "Asian Values." Meanwhile, Christian-based groups have continued to spread mis-information in the mass media, undermining safe-sex education by claiming that condoms are ineffective in preventing the spread of HIV. It is curious how little effort the Health Ministry exerts to correct such mis-information when its own efforts to promote condom use among registered female prostitutes in Singapore have shown huge success in preventing the spread of HIV and other sexually-transmitted infections (Wee 1996, Wong, Chan & Koh 2004). A recent study has even shown that condom use among Singaporean men decreases when they patronise sex workers overseas who are not as well trained as those in Singapore in initiating condom use (Wong, Chan & Koh 2006). There is no credible scientific research disputing the strong causal link between condom use and lowered STD and HIV infection rate. There is no reason why science should take a back seat to sex phobic religious ideology in matters of public health.

Fear of community associations and mobilisation

Forming community associations to advocate for changes in government policies is another stigma pertinent to HIV policy in Singapore. Although some may claim there has been lessening of this stigma in recent times, the 'anti-government', 'trouble-maker', 'partisan player in politics' and other variations of these labels are still being used by government spokespersons and are very powerful signs to mark and silence those brave enough to speak up (Bhavani 3 July 2006). Singapore society is also on the whole complicit in accepting such a state of affair, preferring to "toe the line" than to "rock the boat." This stigma has been so well internalised by Singaporeans that self-censorship becomes prevalent and often times unconscious (Gomez 1999). The Singapore state has also cleverly maintained a public discourse of "liberalisation" to mask the working of this state-imposed stigma (Tan, forthcoming). Consequently, social innovation and change are continually being arrested and community-based organisations (except those approved by the state) generally operate at much reduced capacity and efficacy. Until such time when the Singapore state is willing and able to jettison such tight social control, or when Singaporeans are no longer willing to be controlled in such manner, changes in HIV policies will be slow.

What happens if Public Health Policies are infected with stigmatising prejudices?

Without being exhaustive, public health policies infected with stigmatising prejudices generally exhibit three major characteristics: Denial, Blame and Punishment.

Denial

Denial is the wilful refusal to face reality. A strong form of denial is the suppression of truthful reporting which China used to engage in (Actupny.org). A weak form of denial is to ignore or take no action in the face of epidemiological data. For example, the incidence of Sexually Transmitted Infections (STI) among the 10-19 age group is showing a sharp rise in recent years (Sen, Chio, Tan & Chan 2006). This means that a fast increasing number of teenagers are having unprotected sex. However, the Singapore government continues to push abstinence as the only means to protect teenagers from HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases (STI) and to date, the Ministry of Education still prohibits sex educators from giving information about condom use in schools.

Blame

Blaming has the effect of relieving the government of responsibility because it is "their own fault" when adults get infected. This creates a class of inferior and stigmatised people who receive minimal help, and a class of superior and complacent people who think they cannot get HIV.

"Ninety-three percent of the cases are men - with two significant risk groups - gay men and lower-educated single men who have casual sex with sex workers abroad." (Sadasivan 2005)

The category "Risk Groups" has a hidden message of blame. In this case, they are gay men and lower-educated single men. The blame then subliminally justifies indifference to the suffering of these marginalised communities because they deserve it. The impression it creates is that if you are not in the marginalised community of gay or lower-educated single men having sex abroad, you are not among the "risk groups" and therefore quite safe from HIV. The reality is that everyone who engages in "High Risk Behaviours" can get HIV, regardless of sexual orientation, education level and marital status (7).

A more insidious damage that "risk group" terminology causes is the difficulty in talking about married women at risk of infection from their philandering husbands. How does one classify that high-risk group? "Married Monogamous Women?" This example clearly demonstrates that "risk group" is useless as a conceptual tool. Its only real use is for blaming people who are HIV+ and encouraging the discourse of "innocent victims." The result of this stigma is that instead of creating a comprehensive AIDS fund to tackle the lack of funds for HIV treatment as originally discussed in public (Channel News Asia 19 Aug 2005), MOH created instead a fund only for women and children (Channel News Asia 5 Dec 2005).

The complacency that results from this "risk group" terminology also underpins the refusal to educate teenagers about safe sex, because "these are our good children" and not like those horrible homosexuals. So they must be protected from all knowledge of sex lest they be tempted.

A very simple change in terminology is to talk about high-risk behaviours among subgroups. For example: married women who suspect their husbands of having unsafe sex outside of their marriage but do not negotiate either male or female condom use. Or: gay men who have multiple sexual partners but choose to engage in unprotected anal sex.

Punishment and Neglect

Punishment can take many forms. The most extreme of which is the proposal to criminalise all HIV transmissions, whether knowingly or unknowingly. Fortunately, this proposed law now appears to be dead. Another is the ruling for many years that those who died of AIDS must be cremated and buried within 24 hours. Fortunately too, due to the efforts of the staff and volunteer caretakers, this ruling has now been lifted (John 20 March 2005). Overall, we can be thankful that although punishment looked for a moment as if it could get a lot worse, good sense eventually prevailed and there is now much less punishment in government policy dealing with HIV than previously.

Neglect includes refusal to subsidise HIV drugs within the public health system, few programs and little funding for the care of PLWHA (John 20 March 2005), and refusal to allow de-stigmatisation media campaigns despite several civil society initiatives in this direction. These problems are still outstanding.

What are the social costs of stigmas?

Stigmatisation affects everyone, not just PLWHA. Both PLWHA and society pay a heavy price when public health policy is influenced by stigmas and prejudices. Some of the social costs of stigmas are listed below.

Higher mortality rate

When PLWHAs are rejected by families or shunned by friends, they often internalise these stigmas, resulting in demoralisation. One common result of demoralisation is that PLWHAs refuse to seek medical help or stop taking their medications. Coupled with the less than optimal care the public health system provides, the mortality rate of PLWHA becomes higher than it needs to be.

AIDS Orphans

Since about 75% of Singaporeans who are HIV+ are heterosexuals, many of them would have family and children, a high mortality rate among them means that current policy is unnecessarily producing AIDS orphans. The ravages of stigmas affect not just Singaporeans who have HIV/AIDS, but their children as well. Do we as a society feel that it is justifiable for these children to lose their parents?

Understatement of prevalence rate

To avoid being marked by stigma in Singapore, people would either refuse to test or go overseas for their HIV test. They would also avoid contact with any local HIV agency so as to keep their status secret. Finally, they would also go overseas for their medication since medication in Singapore is much more expansive. The greater the stigma, the more prevalent will this behaviour become. Left unchecked, it can lead to gross distortion of epidemiological data, making the officially measured prevalence rate much lower that the real rate. This falsely low rate will in turn lead to complacency, and allow the epidemic to spread unnoticed.

Diminished effectiveness of prevention

With strong stigmas and taboos operating in society, the ability to conduct effective intervention becomes compromised. This impact happens on two fronts. First, when there is unwillingness to collect data to determine if the abstinence message is reducing infection rate, it becomes very difficult to objectively evaluate if it is effective. It also becomes very difficult to design other more effective interventions. Second, stigmas cause the affected population to hide thus making it more difficult to reach out to them to discover the truth regarding what social norms are driving their continual practice of unsafe sex. Without accurate knowledge of people's motivation for unsafe sex, we cannot devise effective messaging to persuade them to change their behaviour.

Loss in human productivity & decrease in GDP

According to CDC Atlanta: "people with HIV and AIDS are living longer, healthier lives today, thanks to new and effective treatments" (CDC 5 May 2006). However, these effective treatments are expensive without government subsidies and many Singaporeans cannot afford them. Singaporean PLWHAs without access to optimal treatment and care are less able to live healthily and continue working. Stigma in the work place can also make staying on difficult. Such loss in productivity has a negative impact on GDP. The loss in GDP could well be much higher than the cost of subsidising medication. The government needs to undertake studies to determine the cost effectiveness of subsidising HIV treatment if it wants to justify withholding such subsidies.

Breakdown of family

Stigmas can lead to families rejecting one of its members for being HIV+. When families refuse to support PLWHA dealing with the devastating physical and psychological effects of the virus, and unless Singaporeans are willing to let these people die in the streets, society will end up having to foot the cost of shouldering this responsibility.

Increase in sexual exploitation of children

Without comprehensive public education program about condom use, men who want to continue practicing unsafe sex go to neighbouring countries to sexually exploit children in the belief that they are 'clean' (Chong, 30 July 2005; Muntarbhorn 30 April 2005). According to Chong's news article: "A recent Johns Hopkins University study reported that Singaporeans form the largest group of sex tourists in the Riau islands, including Batam, and where most of those exploited are under 18." Stigma and ideology, often underpinned by a sense of moral superiority, have, ironically and tragically, led to Singaporeans engaging in sexual exploitation of children in the region. The social costs of this particular impact of stigma are especially heinous and preventable.

Export and re-import of HIV

After spreading HIV and STD to children in Batam or Bangkok, other Singaporeans men going there will pick up the diseases in turn and bring them back home. This introduces a whole host of complications in tracking the epidemiology and the treatment of HIV in Singapore.

Rising STD infection rates among teenagers

When denial of teenage sexuality is firmly in place, there is only official data on teenage STI infections when they seek treatment but no official data on their condom use. There is also firm reluctance to carry out safe sex education for teenagers. The result of this policy is very likely to be an increase in infection rate among teenagers in Singapore, and STD rates among teenagers are in fact rising (Sen, Chio & Chan 2006).

Lack of funding to treat HIV

With the government reluctant to fund HIV treatment for all, the alternative is to seek private donations. But the public is generally reluctant to donate because the disease is so stigmatised. The cost of stigma is limiting the government's option of letting private donations pay for the cost of HIV treatment, making such an option less effective than it could otherwise be (Soh 1 Oct 2005) (8).

General reluctance to collaborate in HIV prevention efforts

After a bad start, MOH is now implementing a program that aims to do effective HIV prevention: It is encouraging companies to provide HIV education to employees in their place of work. This is a good start as normalising HIV education in the work place will help reduce stigmas and begin to eliminate some of the costs that I have listed above. Unfortunately, it must now do battle with prevalent prejudices and stigma. Most companies in Singapore have so far refused to provide free MOH- sponsored HIV education for fear of being tainted in some ways with AIDS (Ng, 27 September 2005). Ng reports that according to Mr Benedict Jacob-Thambiah, who is the man providing this service, "Only 13 out of 200 companies he calls are keen."

Footnotes and references for this essay can be viewed in PDF format by clicking here.

In part 2 to be published this Friday, Dr Tan looks at pragmatic and successful public health policies adopted by other countries, and what both the government and the people can do many things to counter stigma in Singapore.

Dr Tan Chong Kee holds a Ph.D. in Chinese Literature from Stanford University in the United States and is one of Singapore's best-known figures in civil society activism.