"Where would I possibly find enough leather

With which to cover the surface of the Earth?

But (wearing) leather just on the soles of my shoes

Is equivalent to covering the earth with it.

Likewise it is not possible for me

To restrain the external course of things;

But should I restrain this mind of mine,

What would be the need to restrain all else?"

- Santideva, 8th Century C.E. Indian Buddhist sage

On this recent Christmas Day, I was invited to an all day brunch-lunch-dinner affair at a friend of a friend's house. All in all, it was a festive, laid back, and non-alcoholic Christmas gathering. The kitchen table was rich with home-cooked items, like meat pies, broiled shrimp, mashed potatoes, pumpkin pie, and roasted chicken, among many other delicious dishes. The television in the kitchen was switched on a channel broadcasting a Filipino variety show, featuring lots of singing and dancing to Christmas tunes in Tagalog.

The young folks in the house ended up crowding in the living room to play a game on the host's Nintendo Wii console. The game we played was the most recent version of Super Smash Bros, a game in which you pick a character to play from a whole series of available Nintendo characters, each with their own special abilities, to combat your friends in lush worlds.

Four of us had been playing this game for about an hour, when another person arrived at the party, a friend of the host, who promptly sat and joined us on the couch with his eyes also affixed on the television screen. Midway during the game, he commented on one of the characters' special powers, "Ha ha! That's so gay."

I felt the hair on the back of my neck stand for a split second. I quickly shrugged it off and tried to ignore his comment, but unfortunately, that was not the last time I heard that word "gay" used in that way that afternoon. Soon, a few other folks in the room started using the phrase, "that's so gay" very liberally to describe things that they did not like, or just found pathetically amusing.

I felt increasingly uncomfortable, and exchanged glances with my friend, whom I believed also felt unnerved and annoyed by the phrase. I could feel my frustration and irritation arise in me, but I was at least as threatened by my own inability to speak up about feeling uncomfortable. I felt upset about all our collective silence on the issue. I did not feel comfortable challenging the way the word "gay" was being used to mean something bad. After all, I was in a relative stranger's house (to remind, this was the house of a friend of a friend) so I instead opted for the easier route of deciding to leave.

And so, with much tact and apologetics, my friend and I bade farewell to the otherwise welcoming Christmas party, our bellies filled and fully caffeinated on soft drinks, and our minds frazzled by the Nintendo and the awkward social encounter with that damn phrase, "That's so gay."

Santideva was an Indian monk and scholar of Buddhism who lived in the late 7th and early 8th century, orator of the famous epic, the Bodhicaryavatara, or the Guide to the Way of the Bodhisattva, one of the epics in Mahayana Buddhist literature. In the Guide, Santideva famously espouses a theory of ethical training which challenges us to go beyond our ordinary ways of dealing with conflict (in which we only blame others or try to change others' behaviours) suggesting that one of the major roots of suffering is in our very selves.

In this case, it was not only that the phrase "that's so gay" is the problem, nor is it even that the people who uttered the phrase are the problem, but that it is also true that I am accountable for my own anger and frustration. From Santideva's perspective, he might suggest that in order to adequately address other people's offensive speech, we should also address the seeds of anger, resentment and self-shame that offensive speech simply waters.

Santideva, of course, did not grow up a young gay man in the 21st century, and yet his words strike a chord with me. If I had tried to pave the planet before I could walk in it, it would be a limitless and impossible task. And yet, if I just wore shoes, it would be as if the world was thus paved. Similarly, if I tried to curtail every oppressive, homophobic, racist, sexist action that everybody did everywhere, it would likewise be a limitless and near impossible task.

And yet, the revolution can begin in my own mind. Firstly, I must address my own negative emotions that arise in the face of such offensive speech/behaviour. In this case, I left the space in which I was feeling uncomfortable, so that I would have time to reflect on the emotions that the space was engendering in me. Secondly, I must address the ways in which I have myself been complicit in maintaining inequality.

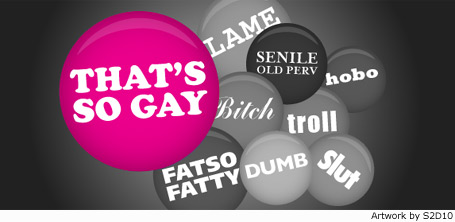

For example, terms like "fatso" or "fatty" suggest that we are preoccupied with some idea of physical normalcy/beauty (such as skinniness). Many of us use terms like "dumb" and "lame" quite frivolously to refer to things we do not like, words which have their roots in thinking of physically disabled people as less than human. This very belief that has been one of the roots of the Nazi Holocaust which featured the mass extermination not only of Jews and homosexuals, but those who were seen to be physically and/or mentally handicapped. My guess is that most of us who feel most comfortable using terms like "dumb" and "lame" are not likely ourselves "dumb" (mute) or "lame" (physically disabled).

Some people use the term "bitch," some gay men use this term to each other, without thought about how this term has historically been used to put women down. The word is usually used in reference to women who are strong-headed or tough, qualities that are usually rewarded in men. Growing up in Singapore, I would hear terms like "chow chee bye," a Hokkien term that roughly translates into "smelly vagina," used to describe someone whom one did not like. Annabel Chong, one of Singapore's most famous pornographic exports who broke a world record being filmed having sex with about 70 men in 10 hours in 1995, points out the double standard applied to men and women regarding sex. According to Chong, if a man had done what she had done, he might be admired and called a "stud." And yet, because she was a woman, she has been called a "slut." Those two words in the English language have different ethical connotations, both of which are solely determined by gender.

Aside from gender, there are many other ways that we expose our own biases, prejudice, and ignorance by the way we refer to other people. Sometimes, when we want to put down somebody's behaviour or actions, we tell them to "grow up," and sometimes older folks refer to younger people as "kids," as a way either to demean or patronise the intelligence, insight, and life journey of younger people. Many younger people, in turn, have come up with terms and phrases like "troll" and "senile old perv" to demean the sexuality and wisdom of older people. For some of us who live comfortably, we do not think twice about saying things like "that's so ghetto" or "hobo" to describe things we do not like, even though those terms have their roots in demeaning people who live in conditions of poverty.

It may seem that I have become obsessive in attempting to describe all the myriad of words that have very specific hurtful connotations to certain groups of people. What is the point in all of this? you may ask. This is all too much! How can I possibly be fully conscious about the implications of every little thing or word that I say, for fear that I may hypothetically, accidentally hurt one person's feelings?

Yet, if we are serious in asking others to stop using words and engaging in actions that are homophobic (and I believe we should continue to challenge people on this very issue), I believe that we also have to bear witness to the very ways in which we challenge ourselves as individuals and as members of an increasingly global community. We have to address the very roots of anger and hatred, our fear of losing our physical vitality, our fear of femininity, our fear of sexuality, our fear of aging, our fear of poverty, and so on, which characterise the very mental roots of any and all of our epithets that we use to demean others. After all to what extent can we ever opt to demean or make ironic jokes about something or someone without resorting to words that have their basis in social inequality?

It is here that I disagree with Santideva's conclusion as it applies to speaking out against hateful speech or injustice. He suggests that once we have restrained our minds, "What would be the need to restrain all else?" But I am suggesting that it is especially when we have been able to restrain our own minds, that we will be better equipped and able, indeed, responsible for helping others restrain theirs.

Let us, this New Year, as a community effort to address homophobia, also focus on challenging ourselves not to use words that can hurt others. Let us challenge ourselves on our own ignorance with regards to race, ethnicity, religion, gender, sexual expression, age, body type, physical ability, national origin, and so on. Let us be more mindful and resolve to support each other, and support the diversity that is in our community. At the same time, let us also challenge ourselves this year to speak out compassionately against the ignorance that we see in others, without resorting to demeaning their humanity.

For if we are able to be successful in this, even if in the tiniest of steps forward, that would truly be so gay.

Malaysia-born and Singapore-bred Shinen Wong is currently getting settled in Sydney, Australia after moving from the United States, having attended college in Hanover, New Hampshire, and working in San Francisco for a year after. In his fortnightly "Been Queer. Done That" column, Wong will explore gender, sexuality, and queer cultures based on personal anecdotes, sweeping generalisations and his incomprehensible libido.

2 Jan 2009

''That's So Gay''

Along with frequently used insults "bitch" and "slut", "that's so gay" has joined the club and is used by schoolchildren and adults alike to put others down. Shinen Wong reflects on the use of commonly used slurs by gay and straight people alike.