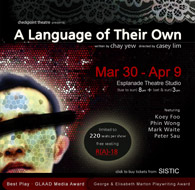

This show was bloody marvelous. We had convincing, heart-rending performances from the leads, a minimalist staging that was subtle, yet strongly moving, and a mind-blowing script from �migr� Singaporean playwright Chay Yew.

I was pretty wary when I heard the billing of Language as a play about gay Asian-American men, because it's so easy to do a gay play as a display of gratuitously topless boys wailing about homophobia, or an Asian-American play as a parade of model minorities wailing about racism and cultural displacement. Victimhood's an easy game to play, and it's got some power on the level of activism. Ultimately, however, it tends to produce only mediocre drama.

Yet A Language of Their Own manages to escape the clich�s of this angst-fest by displaying what gay Asian Americans do to each other. Consequently, it's less about sexual or ethnic politics than it is about relationships - how love and breakups rend our beings apart, and how lovers leave their cultural marks on each other, transforming one another long after bonds are broken. It's a strikingly moving performance for anyone, and doubly so for those of us who're gay and Asian.

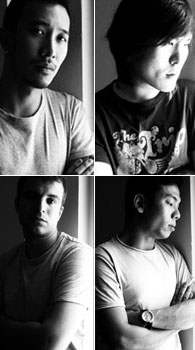

The two leading lads are the lovers Oscar and Ming, played by Koey Foo and Phin Wong respectively. They're particularly interesting in terms of how they've constructed their identities as modern Asians, since the key difference between them is simply how Oscar was born in Asia and grew up American, whereas Ming was born in the U.S. Oscar's Americanness thus fits uneasily, like a mask, while Ming is a dyed-in-the-wool Western culture convert. It's a crucial contrast that's played out in their emotional conflicts, a battle between Oscar's "traditional" Asian emotional reserve and Ming's confrontational in-your-face attitude. As they declare, "The only thing we have in common is that we're Chinese. The only thing that draws us apart is that we're Chinese."

Then the tragedy strikes: Oscar discovers he has HIV, and initiates a breakup. This starts off a volley of questions, lingering in the audience's minds throughout the play: Who's to blame? Is either side really at fault for the hurt that we cause those we love? What's the right thing to do when one party in a relationship is much more vulnerable than the other? The play's written at the a time when HIV was at much higher levels in the American gay community, but director Casey Lim's staging uses the disease less as a topical issue than as a catalyst to display the nature of loving relationships, how we love and break up and rend each other apart in the process. The fact of AIDS is accepted in the play as part of the cultural landscape of gay life, just like open relationships, bathhouses, occasional cheating. It doesn't apologise for the differences between gay male relationships and straight ones. Instead, it lays bare the souls of the characters, so that we understand and identify with them more than we judge them.

There's a level of excellence in this first half of the play that's gemlike - it's just the two of these boys on stage, and the director's intensified their emotional distance by having them stand stationary, addressing the audience, only rarely breaking out of these postures to meet one another's faces. The lights subtly shift to make them alternately dark centres of pain in the middle of illuminated oblongs to open, vulnerable creatures in a wash of light.

And the acting of these boys - it was incredible, especially considering how they had to hold our attention without props or costume changes or even much physical action for half the play. The intensity of their stage presence, their believable chemistry, their weeping eyes that could run like faucets - it just floored me. Even though I hadn't liked Oscar too much at first, I warmed to that emotionally inhibited hunk until all I wanted to do was lick that obscenely protruding belt-strap of his, throw him down on the stage and fellate that repression right out of his system, virus or no virus. It's a mark of quality, I think, if a play makes you hot for a character without making him undress.

Compared to this level of performance, the quality of the later half of the play seemed to dip as it featured the intrusion of two more characters - especially as these actors' talents were eclipsed by those of our heroes. Peter Sau, as Oscar's foreign student boyfriend Daniel, was joyfully camp but never quite managed to sound as sophisticated as is dialogue demanded, while Mark Waite, as Ming's white boyfriend Robert, only seldom showed signs of developing as a fully-blown character beyond the surface text of his speech.

Nonetheless, the presence of these rebound squeezes was essential, since it let us to see how Oscar and Ming's relationship extended beyond the termination of their romance. A few especially painful moments popped up as we realised how each had affected the other's approach to love quite permanently, Oscar in particular trying to become the person that Ming had wanted him to be.

I won't give away the ending of the play, but when one character has HIV, you can guess that it's not going to be all balloons and kittens. Suffice it to say that the cute couple next to me in the audience were sniffing for their pocket tissues by the end of the show, and even if you're not the weepy type, you'd better prepare to be profoundly moved. But what you carry away from the play isn't a sense of devastating loss - it's a solemn reflectiveness on the difficulty of love, its beauty and its wonderful, inescapable scarring.

A Language of Their Own was banned in 1995 when Theatreworks tried to stage it in Singapore, and I'm pretty sure it was partly because it's a play that only features gay men, taking the validity of our relationships as a given. There's no excuses, no guilt, no distressed Confucian parents. Instead, it shows us behaving badly to each other, harming and betraying each other as much as we love and support. Maybe that's the real danger to heterosexual society: the fact that plays like this can move the straight kid in the street to accept gay life, with all its differences, rather simply tolerating the abstract concept of homosexuality.

Chay Yew's come a long way since 1989, when the censorship boards of Singapore banned the first play he wrote because the gay lead character was too "sympathetic and straight-looking." Rather sensibly, he kicked us to the curb, went to the States, and became the playwright on gay Asian-American issues - Chay Yew: 1, Small-Minded Nation-State: 0.

It's a hell of a good thing he trusts us all these years later to breathe life into his work. And it's a hell of a good thing that we've been able to do justice to his piece. Go see this show: laugh, cry and reflect. It's a mark of the times: we don't have to feel sorry for ourselves anymore.

Director: Casey Lim

Cast: Koey Foo, Phin Wong, Mark Waite, Peter Sau

Tickets @ $33 (excludes $2 SISTIC fee)

Available from all SISTIC outlets

SISTIC hotline: 6348 5555 or book online at www.sistic.com.sg