In the fifties and sixties, when Christopher Isherwood wrote scripts for Hollywood films, no one, neither film star nor script writer, was out, so on that ground alone he would have been amazed at the screening of Tom Ford’s film of his novel, A Single Man. Immensely encouraged, too, one could imagine, by the way the world has at long last changed, for in putting Isherwood’s tale of gay love, partnership and grief onto the screen, Ford has hidden nothing of the author’s intent, and in the process has made an arthouse classic.

We forget now what it meant nearly fifty years ago, when, in 1964, Christopher Isherwood published A Single Man. We remember Isherwood’s life and venerate him as a gay icon but this in retrospect can dull the revolutionary effect made by his profession in print of himself as a gay writer. His Berlin novels and his subsequent writing had given a pretty good indication of his sexual orientation, but only to those who knew where to look, and until A Single Man he had not written a book which made it plain.

A Single Man not only did make it plain but did so in a way deliberately designed to show the world that gay love was ordinary, commonplace, natural. Remember that this was three years before same sex acts were first decriminalised in England and that it was a time when California, where he wrote and set the novel, especially in the Hollywood where he worked, was in the full post-McCarthy state of denial in which it was to remain for another decade.

In the States, only Gore Vidal’s The City and the Pillar had struck out a similar lonely path back in 1949 and the cost of writing that for Vidal had been exile from America’s literary firmament for a generation. A Single Man was a gut-wrenchingly brave book and it would alone justify Isherwood’s reputation as a gay pioneer.

Colin Firth (top of page) plays George Falconer, forty-something Englishman, professor of English (as was Isherwood) at a Los Angeles university, whose partner of sixteen years, Jim (Matthew Goode, of Brideshead Revisited), has died in a road crash in another state, a road crash of stark, icy beauty shown to us in the dreams George suffers before he wakes to yet another long, echoing corridor of a day without Jim. As the weary day progresses, the closeted compromises and deadly dullness of his now single and, as he sees it, utterly pointless existence are revealed in his interactions with the characters he meets; his loving housekeeper, the students in his class (who are tellingly studying After Many a Summer, Aldous Huxley’s macabre tale of an attempt to prolong life), the young Spanish hustler he meets and almost picks up at the store, and most revealing of all, Charley, George’s flamboyant alcoholic fag hag who has trailed after him from the London of his youth in the unrequited hope that she can make him straight (Julianne Moore in a show-stealing cameo of blousy, frustrated, addled emptiness).

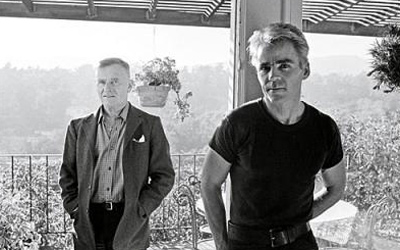

The late Christopher Isherwood (left) and his partner of 33 years,

Don Bachardy. Their relationship, which began in 1953 when

Bachardy was 18 and Isherwood was 48, has been chronicled

in a documentary Chris & Don: A Love Story.

Restraint rules George’s life and governs this film. Ford’s direction and the cinematography of Eduard Grace capture this in every anguished nuance. Grace shades reality in colours that flow from George’s mood, fading in and out of sepia and black and white (past time, the emptiness of the present) into warm, golden colours (the present, that is when it is alive). The art direction matches, period-perfect, as you’d expect from a director who has spent his life defining shape, texture and fashion. He’s aided here by the expertise of Don Bachardy, artist and partner for 33 years of Christopher Isherwood, whose own hand can be seen in the sketches that surface briefly in George’s house and who advised on the film; so much here is redolent of the way that he and Isherwood must have lived. Washing over and through it all is the movie’s sound track, mellow, melancholic music which is an autumnal elegy for lost life. The mixed classical-orchestra and electronic score of the Polish composer Abel Korzeniowski, particularly the main theme ‘Stillness of the Mind’, submerges the film in sorrow.

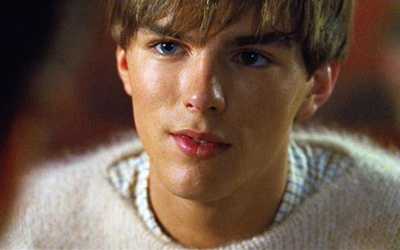

Nicholas Hoult

Not all here is sadness, though. George finds a kind of redemption in the spring of life he sees and falls for in Kenny, one of his pupils, played here by Nicholas Hoult (above; who starred alongside Hugh Grant in About A Boy). Naivety and youthful body combine to restore jaded middle-age in some touching and very sexy scenes late at night in the surf and in the bedroom. Hoult has an Adonis-like derriere!

This is Ford’s first film, though watching it you’d imagine he had spent his life not making a name as a fashion icon but as a director, for it’s faultless. It’s incredible that he shot it in only twenty-one days. Not in the slightest daunted by taking on the interpretation of this gay classic, Ford has had the temerity to alter it and to improve it. Isherwood’s whole point is the ordinariness of gay love and the lifelong partnerships in which it can flourish, and in his book he is at times all too English in bringing home the dullness of George’s existence. Ford adds one or two elements to the plot to bring us closer to George’s suffering without detracting from the theme. I will not elucidate what these are for fear of spoiling the story – read the book after you’ve seen the film and work them out – but I confess to preferring Ford’s adaptation.

Colin Firth and Julianne Moore

Ford does not change, though, Isherwood’s perception that the world is incapable of understanding the reality of George’s love for Jim and of his loss. Charley, of all people, crassly makes it clear in her cups that she fails here, too, and that even after all these years she still regards George’s love as of an inferior nature. George’s neighbours politely do the same, leading to one of George’s (only slightly) unrestrained outbursts in both book and film: "Your [psychology] book is wrong… when it tells you that Jim is the substitute I found for a real son, a real kid brother, a real husband, a real wife. Jim wasn’t a substitute for anything. And there is no substitute for Jim, if you’ll forgive my saying so, anywhere."

A Single Man is already picking up nominations and awards; a standing ovation of a full ten minutes followed its final scene at the Venice film festival and Colin Firth is nominated for Oscar, BAFTA and Golden Globe. Not an easy task, his, to get inside the stuffy exterior of George’s sober, dark suit, his starched white shirt and narrow, dark tie, more, to make him not only human but at times warm, even attractive. His buttoned up sorrow is harrowing, an emotion that chokes both him and us, yet the scenes between George and his lover, Jim, are tender, their love joyful and their domesticity is so natural and simple that it delights. This is, in my view, Firth’s finest piece of acting to date. He deserves to win every one of these nominations.

As does Ford, for creating this achingly beautiful film. He has caused some controversy by denying in public, one suspects for the purposes of the industry and the commercial success of his film, that this is a film with a specifically gay theme, instead pointing to the themes of love, loss and grief which he claims to be universals. He cannot believe this, and this film belies the idea that he could so deform Isherwood’s intent. Ignore the Hollywood spiel. This is a film about what it is to love another man for a lifetime and then lose him. A Single Man is a movie that can stand as a classic on many merits, but the greatest of these is what it says for gay men and how perfectly, how beautifully, it says it.

A Single Man Gala Premiere: Feb 27, Hong Kong

A Single Man is distributed in Hong Kong by Sundream Pictures. There will be a gala benefit showing of the film in aid of the Chi Heng Foundation’s HIV prevention and education work in China at 9.45pm on Saturday 27 February at the Palace IFC. Tickets cost HK$400, including the post-film party at the Kee Club, or HK$2,000 including both party and pre-film dinner. Tickets are available from the Chi Heng Foundation, telephone: 2517 0564 (office hours 10am to 6pm Monday to Friday).

A Single Man Fundraising Gala Premiere: Mar 3, Singapore

Fridae will present the A Single Man Fundraising Gala Premiere on Mar 3, 9pm at The Grand Cathay, The Cathay, 2 Handy Road to benefit the Fridae Community Development Fund. Click here to read more. Standard tickets are at USS$10 and VIP tickets which include a pre-show reception from 7.30-8.30pm and premium seats are at US$30. Tickets are available online on Fridae Shop.