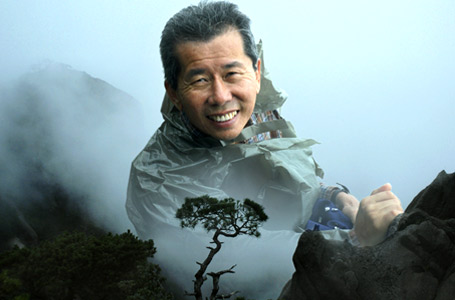

I first met William Yang in 2006 at a Chinese arts festival in Singapore. In the midst of a programme of lion-dancing, wushu (martial arts) and Beijing opera, he was doing one of this photographic performances, describing his life as a gay man while showing off artistic slides of his beautiful multi-ethnic boyfriends (yup, he has more than one at a time).

Weirdly enough, this didn't come across as scandalous at all - he had the unassuming air of a fine old Chinese gentleman, casually intriguing, the kind of guy I always wished I had as an uncle. Talking to him after the show over satay, he only became more interesting: he's a third-generation Chinese Australian, one of Sydney's most respected society photographers, sought after throughout the international circuit for his autobiographical performances.

It's no wonder that he's one of the headliners for Men Like Me, a photography exhibition focussed on representations of gay Asian men by gay Asian men, curated by Garrie Maguire as part of Melbourne's queer festival Midsumma. The other photographers are a motley bunch - there's Michael Shaowanasai from Thailand, Taguchi Hiroki from Japan, Marcus Mok and Yan Tuck Hong from Singapore and Norm Yip from Hong Kong, to name a few. And while I'm sure they're all fascinating characters, in this article, we're going to focus on the much-lauded William.

As a gay Asian living in Australia before the age of political correctness, William's had to deal with racism, crises of identity, being labelled a banana (yellow on the outside, white on the inside), and actually describes having to "come out as an Asian" - accepting and acknowledging his Chinese heritage together with his sexual identity. At the same time, he claims he's managed to be better society photographer because as a Chinese person in Australia, people don't notice him as much.

This past weekend I managed to get a phone call to the man on Sunday, ostensibly to plug the gallery show but really to have the chance to talk to him again:

WY: I'm 64, male; lives in Sydney.

æ: Tell us a bit about your photos in this exhibition.

WY: Well, the centrepiece is a self-portrait I did called Alter Ego (image right). You can read into it what you want, but one of the most obvious interpretations is that it's about how in gay society body image, muscle, gym tone is very important - as gay men, we all long to have better bodies.

Another one is of this Asian couple. I was publishing thirty years of work in a book and I got a call from one of them saying, "Please don't put me in the book because nobody knows about me." So I cut his face out and I wrote in its place the telephone conversation we had. It's called Invisibility No. 1.

æ: Do you feel being gay and Asian has affected the way you do your photography?

WY: I suppose that I've paid more attention to Asian men. In the '90s, there was an issue of gay Asian men never being depicted as desirable within the dominant white commercial framework. So I took more sexy photographs of them, so there would be a kind of representation of them.

But now, as Garry (the curator) has discovered, there's now a proliferation of images of Asian musclemen, so many that it's become a clich�. It's all to do with social change.

æ: But there was actually a period when taking sexy photos of Asian hunks was a political statement?

WY: If you trace the history of gay Asians in Sydney, you'll find that the time when we were most politicised was in the early '90s. That was a time when we felt we had to establish our identity as gay Asians in a predominantly Anglo community, and point out to the wider gay community how we had certain issues, such as how gay Asians usually desired Caucasians, and how in porno magazines Asians were always portrayed as passive, and how there was racism - it could be a simple as the doorman not letting you into a bar because you were Asian.

Mardi Gras had been going for almost 20 years before there was a significant gay Asian presence. Now there's the Asian Marching Boys; they're the face of gay Asians in Sydney. In the late '90s we also used to have a Chinese New Year party as part of Mardi Gras, with both gay and lesbian Asians, and that was quite good for us because it moved from politicising to celebration, and we got a lot of publicity from that. But now they've stopped. Of course, there's always been the special group for gay Asian men who are HIV-positive at the ACON Department.

æ: Those revolutionary days are over, then?

WY: Times change. When I grew up, it was illegal to be gay, and we were all very suppressed - and people of today's generation haven't had to go through all that. The battles have been fought, and they've benefited from that. There's not so much need now for group identification, which is why even Mardi Gras is in a sort of crisis over whether it's relevant anymore.

Now being gay has broader connotations; now people whom you might call straight are identifying as a little bit queer, and it's no big deal. I've noticed this in Sydney. It's really rather nice.

æ: Tell us about your journey as an artist. How did you decide to go into the arts?

WY: Well, I suppose that I'd always wanted to be an artist. But when I was in Queensland University, I studied architecture - it wasn't really an option for me to become an artist because it wasn't within a set of viable concepts of what I could become. But I got interested in drama while I was there, so when I came down to Sydney I started as a playwright. I couldn't make a living doing that, so I started taking photographs.

I worked as a freelance photographer for 15 years, but I was very aware that this was commercial photography, while I was interested in art photography. Eventually, I started to do performance pieces - I did my first photographic performance in 1989, and I realised I was on to a good thing - not every photographer could talk about his slides in the way I do.

æ: Could you tell us a little about those performance pieces?

WY: I've done three pieces about family, both in Australia and China. Several about being a minority within a dominant white culture. But my being gay spills out into all of them; when it's an autobiographical piece, I'm speaking as a gay person. One piece of the nine is 100% gay; it's called Friends of Dorothy and it's about gay society in Sydney.

My latest piece, which I'm touring at the moment, is called China, and it's about my visits to China. I've also done a piece about Australian aborigines called Shadows. As you've said, I'm sympathetic to other marginalised cultures.

æ: I've gotta ask, though, since you've talked about body-worship in gay society - is it difficult, keeping active in the scene as an older gay man?

WY: I suppose that if my whole life was based on how I look, yes, I'd probably feel pretty washed up. But in fact I identify more with being a photographer. And let's put it this way: I still get asked to parties as a photographer, and I'm quite happy to be just watching everything and taking pictures. I've sort of found a way to be part of the community without having to rely on my looks.

æ: What's next for you?

WY: I suppose I'm at a stage in my career where I still take photographs, but I don't take as many photographs. And I still have many photographs in my collection I haven't shown, and I'm trying to find a way to go back and look at certain periods of my work and pull different stories out of them.

So my next piece is based on my photographs of the scene I was in during the '70s and '80s. It's called My Generation.

More of William Yang's works may be seen on his website at http://williamyang.com

Men Like Me can be seen at Off the Kerb, 6B Johnston Street, Collingwood, Melbourne, Australia, opening Monday, January 21 (6 pm to 9 pm) and closing on Friday, February 8, 2008. Gallery times are 12:30 pm to 6 pm Thursday to Friday and 12 pm to 5 pm Saturday to Sunday.

列印版本

列印版本