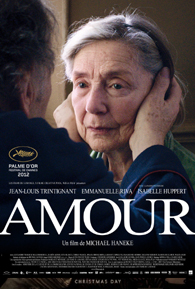

The rest of the film is an account of the wife's slow deterioration from disability to infirmity and senility, the humiliating routine of enforced helplessness and thankless caregiving that the situation enforces on the two, and the conversations both have with each other and their occasional visitors.

As a film about ageing and dying, Amour takes courage to watch because unlike his American counterparts in Hollywood, Haneke doesn't candy-coat the process, put the protagonists on a pedestal, or invent sentimental and dramatic story arcs involving some form of reconciliation with their children that will bring about closure. Whatever dignity there is in dying of old age, of undergoing both physical and mental deterioration — you can look for it elsewhere.

As a film by Michael Haneke, Amour takes courage, patience, and wit to watch because it continues the director's career-long subversion of bourgeois sensibilities. Just like how Funny Games (ostensibly a film about serial killers) also critiqued bourgeois attitudes towards violence and crime, The White Ribbon (ostensibly a film about children who would one day grow up to be Nazis) also critiqued bourgeois attitudes towards evil, Amour is also a critique of bourgeois attitudes towards sentimentality and pity.

These three recent Haneke films are brilliant, narratively economical genre pieces that call out the emotional manipulativeness of their genres so subtly, one can almost miss the director's subversiveness. And as the most visually austere, emotionally draining piece whose genre criticism is the most subtle by far, Amour fully deserves its accolades and film awards.

列印版本

列印版本