Another barrier for Korean queers was shattered this month when Choi Hyun-sook became South Korea's first openly gay candidate.

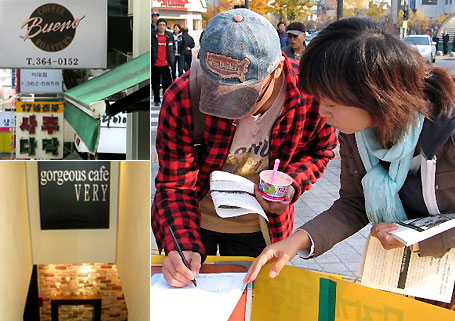

Choi, 51, is the chair of the Democratic Labor Party's coalition of civic groups for sexual minorities, and is campaigning to represent Seoul's historic Jongno district. At a news conference earlier this month, she announced her candidacy for the April 9 elections and vowed to confront political corruption and discrimination against women and minorities.

Choi told reporters that she would "engage in political work for all citizens, not just for the minorities," and that her personal experiences enhance her qualifications.

She said: "Some may question the suitability of appointing a divorc�e who is a lesbian as a member of parliament. But it is exactly the minority who have been through hardship who will appreciate the real politics and spirit of rendering public service to the majority, and to put the policies into action."

Although Choi came out of the closet shortly after her 2004 divorce, it is only recently that she has spoken openly with the press. Her public acknowledgment coincides with an unprecedented mobilisation by Korea's iban, or LGBT community in recent months.

Last fall, business and conservative Christian interests pressured the South Korean Ministry of Justice to remove gays, lesbians and six other groups from a historic non-discrimination bill that was being considered by lawmakers. Choi participated in a series of protests, international media outreach and community meetings to get the protections reinstated. The ensuing controversy forced the bill's withdrawal for additional review. Although the legislation remains in limbo, LGBT activists fear that South Korea's new right-wing president, Lee Myung-bak, is no friend to sexual minorities.

It may be surprising that Choi and others' efforts on behalf of LGBT Koreans are not universally embraced by their intended beneficiaries. Zoe Kim is a 20-year-old student at Ewha Womans (sic) University. At a coffee shop popular among young lesbians near her campus, Kim says that while she was inspired by Choi coming out, she, and many young Korean lesbians like her, are wary of anything that brings a spotlight to their lives.

"We're really secretive and like it that way," Kim says about her lesbian coterie.

Like most gay Koreans, Kim remains in the closet and uses a fake name even among her queer friends. She says that the older generation are not ready to accept homosexuality. Although she wishes she could snap her fingers and instantly make Korea as gay-friendly as some Western nations, her life as a Korean lesbian is generally comfortable, and she doesn't want to come out. "I don't really see the need of lesbians to become [activists]," she says.

It is, however, thanks to the work of queer activists that Kim and other women can enjoy gay social outlets on the peninsula. It was only 16 years ago that Sappho, Korea's first organisation for lesbians, was established by a group of nine expatriates who were living in Seoul. In the mid-1990s, other organisations were formed, newsletters and magazines published, and Korea's first lesbian commitment ceremony was performed in 1995.

Today, in addition to scores of venues for gay men, there are at least one dozen Seoul caf�s, bars and clubs that cater specifically to lesbian and bisexual women. On Friday and Saturday nights, one hundred or more of them gather at Lesbos, Labrys, Pink Button and other venues in the Hongik University neighbourhood of Western Seoul. On the Internet, Korean lesbians connect via websites like miunet.co.kr. In addition to perusing member profiles and exchanging emails, visitors can set up "beong gae" or offline group meetings.

Unlike some of its Asian neighbours, South Korea has no history of laws banning homosexuality, yet widespread ignorance and bias contributes to a hostile cultural climate for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people. As evidence of this, a 2005 poll of 507 Korean women conducted by the Lesbian Rights Research Institute, found that 83 percent reported experiencing discrimination or disadvantages because of their sexual orientation.

Yun Ga-hyun is a professor of psychology at Chonnam National University in Gwangju, who has studied Korean attitudes about homosexuality. Next year, he will publish a paper examining how those attitudes are changing, but in a previous book, Yun argued that Korea's culture perpetuates misperceptions about homosexuality.

Such misperceptions, of course, extend to the families of queer Koreans, so last September, the Korean Sexual-Minority Culture and Rights Center organided the first-ever public forum for the families and friends of Korean homosexuals. One of the panelists was Takako Otsuji, who is the mother of Japan's first openly gay politician, Kanako Otsuji. Otsuji said that it is common for the parents of gay and lesbian children to also experience alienation from their peers. To address this issue, Otsuji and her daughter created a support group for the family and friends of sexual minorities in Japan.

Parliamentary candidate Choi also attended the forum, and she encouraged participants to move beyond the goal of emotional support to political empowerment. "This forum should be a starting point to use our collective power to make legislation to help this community in the long run." She added, "Family is important but so are our basic rights."

Of course, if Choi's bid to join South Korea's National Assembly is successful, she will be in precisely the right position to legislate on behalf of achieving basic rights for millions of LGBT Koreans.

Matt Kelley is a gay mixed-race Korean-American living in Seoul. He is currently writing a book about the intersections of race and sex in Korea. His website: www.mattkelley.info.

打印版本

打印版本

读者回应

请先登入再使用此功能。