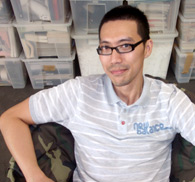

We’re all still mad about the censorship incident at the Singapore Biennale, but that’s no reason not to celebrate the many other talented queer artists in the exhibition. For instance, we’re way overdue for an interview with the extremely accomplished Singaporean artist Michael Lee.

Based in Hong Kong from 2007 to 2009, he’s been creating both overt and subtle gay art over the whole of the past decade, in genres ranging from painting to video to photographic installations. His Biennale work isn’t terribly gay – Office Orchitect, tucked away in Old Kallang Airport, explores his obsession with architecture instead, taking the form of greyboard mock-ups of proposed drawings by K S Wong, a fictional deceased Singaporean architect.

I do recommend you take a peek, though, as I do regard it as one of the best works in this exhibition space. (For instance, it includes a building in the shape of copulating slugs. What’s not to like?) I was able to get a queerer perspective on Lee’s life and work when I dropped in at his spanking new studio space in Goodman Arts Centre at the former Lasalle campus in Goodman Road in Singapore.

æ: Age, Sex, Location?

Michael: 38, regularly, Tiong Bahru, Singapore. (Taken. Don’t cry.)

æ: Tell us a bit about your background. How did you get involved in art?

Michael: When I was 10, I did loads of maths. In university, I made loads of videos. Meanwhile, I came loads.

æ: And when did you come out?

Michael: I started hanging out with fellow junior cCollege mates who were Madonna fans. Enough said.

æ: What was your first work of gay art?

Michael: In 1997, I worked with two classmates on a video on the homosexual community in Singapore. It was called One Or Zero. That video was featured around the world, and bagged the first prize in the experimental category of the United Film and Video Association Student Film Competition. It was banned in Singapore, for condoning an “alternative lifestyle.” In 2001, however, I did exhibit it at Nokia Art Singapore, by showing it in a small box and placing at one end of a cubicle. Today, the original video is still banned.

æ: One of your classic gay works I remember was Three in One (2001), which earned a commendation in the UOB Painting of the Year Competition in 2001.

Michael: I was trying to do two things there: to make a painting that was presentable to the judges and the public, and to work out a way to show pornography in a disguised form. Another early video work A Thesis on Cruising (2001-2003), was more explicit. Videocam in hand, a protagonist stalks good-looking men in London. This was shown on three screens, in and out of which these men appear, simulating the cruising experience.

Stud House (Staircase view)

æ: What artwork would you say you’re proudest of?

Michael: I like all of them for different reasons. But the most seminal would be Stud House (2003). It was an architectural model of a house designed for a gay couple. The question I was dealing with was, “How do two persons live with each other without getting sick of each other?” The house comprised two annexes, two mutually exclusive houses that interlock (think: 69-ing couple) into a perfect cube. In this architectural model are blackwashed Tom of Finland figures. I began making models here, which eventually influenced my works leading up to the Biennale.

æ: How did your work progress after that?

Michael: The body was a recurrent motif, especially in my self-portrait series (e.g., Skive: A Worker’s Guide, 2005/2007) of cutouts of myself in different guises: salaryman, plumber, construction worker, technician… The creative process involved sculpting my body in the gym. Slowly, I moved away from the motif of the body and featured more architectural forms. In 2006, I made City Planned: Tracing Monuments, a series of white models of demolished or collapsed buildings of Singapore. From 2007, I started making book sculptures such as The Consolations of Museology (2008), a series of 10 book-museums that console human beings of their perceived failures. The architectural print series Second-Hand City (2010-2011), showcased at the Shanghai Biennale 2010, melds sci-fi with urban studies, narrating the lives of buildings and cities. For my Singapore Biennale piece, even though my central protagonist K S Wong (born in 1911 and reported missing in 1982) is documented to have written love poems to a girl, in the context of his generation, it would be entirely possible that he was acting out the role of a socially acceptable straight man whilst harbouring homoerotic desires. I like to keep his sexuality ambiguous, just like the sexuality of an infant, or as Freud would put it, the “polymorphous perversity” of a child.

Office Orchitect, tucked away in Old Kallang Airport, explores his

obsession with architecture instead, taking the form of greyboard

mock-ups of proposed drawings by K S Wong, a fictional deceased

Singaporean architect.

æ: Do you think your sexuality has helped you to be a better artist?

Michael: All this saying that homosexuality leads to creativity is bad reasoning, if not outright rubbish! So many of the people working in the creative scene I admire are straight, and they’re hypersensitive and innovative. People like [playwright/director] Paul Rae – I get a hard-on when I watch his performances. So to me, the sexual orientation of the creator – or, for that matter, sexuality or homosexuality as a subject matter – does not matter that much. What helps me grow as an artist is repeated failures.

æ: What’s next?

Michael: I have a solo show lined up in Bangkok later in the year. From June, I will be on Residency programmes, starting with a three-week stint at the Printmaking department of Royal College of the Arts, London. I’ve an Arts Creation Fund grant from the National Arts Council to do research on Singapore’s industrial heritage. The project’s working title is Factory: My Prodigal Child. I’m aligning that proposal with my current methodology to craft the fictional biography of another lost hero of 20th-century Singapore. Hint: He designed sex machines.

You can find more information about the Michael Lee at his website, michaellee.sg. Publications of his work such as Who Cares? 16 Essays on Curating in Asia (2010), which he recently co-edited, are available for purchase at Books Actually, 9 Yong Siak Street, Singapore.

His artwork is currently on show at the Old Kallang Airport exhibition space in the Singapore Biennale which runs from 13 March to 15 May 2011.

Ng Yi-Sheng is a poet and playwright, and winner of the Singapore Literature Prize in 2008 for his poetry anthology Last Boy.

打印版本

打印版本

读者回应

so dull this article:)

gosh singapore needs more gay dads, i hope the future immigration policy specifically targets more gay dads, Singapore has way too many werid childless gay men

if you spend anytime with successful gay dads you will know they only want exceptional art, nothing mediocre like the crap at Biennale, zero artist value, but let the crap be exposed to the light of day, let the censorship die out and let the art critics flourish and good taste will come out on top

请先登入再使用此功能。