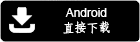

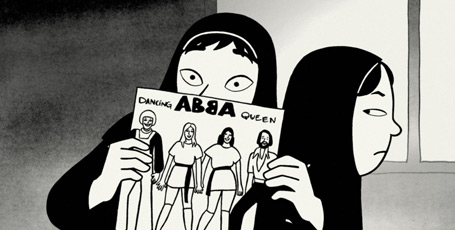

The streets of Tehran were filled with heartbreak and violence, as the Shah of Iran was overthrown and replaced by followers of Ayatollah Khomeini. A self-serving government was overtaken by a group of religious fundamentalists, replacing one oppressive regime with another. The paranoia and fear that followed Persepolis's protagonist - a spirited nine-year-old girl named Marji who would not conform - as she negotiated her way through life, school and illegal private parties had more in common with China's Cultural Revolution than idyllic, peaceful Singapore. Her subsequent exile in Europe brought about a loss of identity and disenchantment, but one final visit to the motherland restored her sense of self and purpose.

A scene where a bunch of young revolutionary police followed Marji's family home to search for liquor can easily echo our fears of being discovered with contraband magazines and videos. Another scene tells of a secret party being discovered by the authorities, the penalty being so severe that risking death was more tolerable - two words: Fort Road. Need I elaborate? (Fort Road was a popular cruising spot from the mid 80s to 90s.)

The most poignant of scenes for me was when a stranger stopped Marji's mother outside a supermarket. He chided her for not wearing her headscarf lower, and when she rebuked him, he shouted, "Why should I respect a woman like you?"� The funny thing was, I didn't just identify with Marji's mother. I could also see a part of me who behaved exactly like the boorish stranger. Honestly, how many of us painstakingly covered up aspects of ourselves deemed 'sissy'? How often did we turn our back harshly on the more effeminate classmates and joined in making fun of them, just to prove how masculine we were? I don't how many of you are like me, but I once went as far as to distance myself from the women closest to me: my mother, sister and nieces.

Many gay boys and girls went through our own personal cultural revolutions. We awakened to a part of us that we felt was unacceptable and weak, and we aligned ourselves with an idealised, unrealistic concept of what a man or a woman should be. The more extreme amongst us banished any action that was deemed effeminate (or masculine, in the case of lesbians): collecting and nursing stuffed toys, expressing our emotions and even good taste in clothes. In the act of trying to look good, we condemn ourselves to living life as incomplete persons.

Fortunately for us, there is hope. Just as we see parallels between the Iran's Islamic Revolution and China's Cultural Revolution in the movie, we also see that cultural and personal rejuvenation are possible if not inevitable. After the destruction and disillusionment brought on by Mao's Red Guards, China began the healing its wounds and is now poised to shine brightly in the world stage. While Iran has yet to show outward signs of regaining its past glory as the ancient great civilisation that was Persia, our plucky heroine survived heartbreaks and disenchantment (to the strains of Rocky's "Eye Of The Tiger" no less) to embrace herself as a woman and an Iranian.

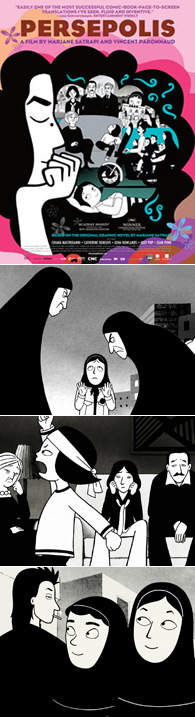

What was not shown in the movie was just as inspiring: the real-life Marjane Satrapi became a successful writer (the Persepolis comic series have been compared to Art Spiegelman's Maus and named by Time magazine as one of 2003's best comic books). Satrapi went on to co-direct this Oscar-nominated, Cannes Jury Prize winning feature film.

While I have so far been harking on about the power of Persepolis's story, I have not forgotten that many of us demand top quality animation too. Rest assured, the animation of Persepolis is as smooth and moody as the modern Batman animated series. The directors are well aware of the advantages of using animation, so what could have been a 6-hour-long pompous epic became a brisk, often humorous and emotionally powerful roller coaster ride. Through it all, never once did the creators let the style overshadow the content.

Oddly, the Iranian government objected to the screening of Persepolis in 2007. The focus of this beautiful movie is clearly not about blaming any political entity. Instead, it did what all great stories do, and presented to the world a facet that political leaders have failed to show us: through the eyes of a comic book Iranian heroine, we saw what is possible in ourselves.

And that is simply more economical and effective a declaration than "we got nukes but no gays in our country."

打印版本

打印版本

读者回应

抢先发表第一个回应吧!

请先登入再使用此功能。