As with the stage play by Ronald Harwood, Beecham House is a retirement home where all musicians go in their old age. They receive the best care available in a sprawling country mansion furnished with rooms of all sizes where they can still keep going at their musical instruments (which makes you think if this film exists in an alternate Britain where a musicians' union takes care of such things). In return, everyone gets to perform something for the annual fundraising for the home on the anniversary of Verdi’s birthday.

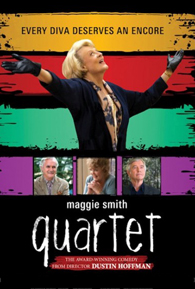

It looks like a very simple deal until the home's new arrival (Maggie Smith as a former opera star) is reluctantly gang-pressed into a reunion with three of her former collaborators (all of whom coincidentally are at Beecham House) to put on an encore of their legendary performance from decades ago.

While the history and dynamics between these characters form the narrative pulse driving the film forward and personal idiosyncrasies that each character adopts to deal with the reality of retirement and ageing, it is the spectre of old age that looms behind the drama and comedy of Quartet. Musicians, it should be noted, are the most affected by ageing. All musicians age like fine wine but beyond a certain age, the body and its muscles loses its suppleness, motor skills deteriorate, and memory fails. Your voice gets creaky, your fingers can't move as fast, and you can't remember what you're supposed to play — and you, a formerly recognised musician with a decent career, have to perform once a year way past your prime?

Quite like The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel before it, the film manages to put a positive spin the physical, private, and social aspects of ageing without sugar-coating the fact that it can be a wretched business. In this sense, Quartet is a reassuring counterpart to Amour.

打印版本

打印版本