An Occasional Orchid

Written by Ivan Heng and Chowee Leow

Directed by Ivan Heng

Performed by Chowee Leow

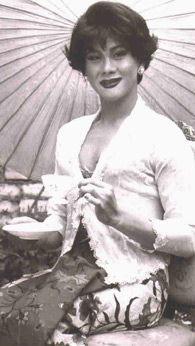

Chowee Leow as Zoe/Joe

Even drag artiste Kumar has ascended the slippery rungs of this patriarchal Confucian state in high heels to be a national icon. Until quite recently, it's the gay men who have been peeping from the shadowy wings while their lipsticked cousins take centrestage.

How unique then is an orchid in an Orchid City, and by extension, a transgender in the context of a theatre history that has seen its fair share of gender benders? Will there be a certain expectation of novelty from a seen-it-all audience? Will Singaporeans, jaded after a long glut of wigs and mascara, finally see the drag in drag?

It is to the credit of both the director, Ivan Heng, as well as the actor, Chowee Leow, that they gave a healthy collagen injection to an issue that would have otherwise shown its tired and sagging features. Dialectical tensions exploded on stage like a violent pollen shower: the protagonist, Joe aka Zoe, was born already a hybrid--as a Peranakan boy, he was part Chinese and part Malay, growing up on a diet of both Pontianak stories (a vengeful bloodhtirsty female Malay spirit) as well as 'babi ponteng' (a Peranakan dish). His venture to London to study medicine added further stresses: he had to negotiate between his Western education and Eastern indoctrination. And needless to say, the sexual conflicts--a woman trapped in a man's body tussling with a man saddled with a woman's psyche.

Opting for a non-linear narrative, the play begins with Joe's Malaccan Chinese father warning him against falling in love with a Caucasian woman, insisting that he settle down with a Chinese girl instead. The irony of course is that Joe follows this advice to the letter--not only does he get acquainted with a Chinese girl called Zoe, but he also falls in love with a Caucasian man instead--a Sinophile by the name of Brian whom he meets at Kew Gardens. It is this Zoe the audience first encounters, an elegant, albeit insecure cock in a frock, as prone to hand-wringing as she is to snapping her fingers and twirling to mirrorball music.

If there was a slight misgiving about the play, it was the inadequacy one felt in Zoe's characterisation. There was little exposition as to how Joe abandoned his medical studies, how he discovered cross-dressing, and even what his immediate social circle was like. But then again, perhaps it was an attempt to frustrate the audience's expectations--the voyeur in all of us would very much prefer to see someone 'becoming' rather than 'being' a transgender.

Chowee Leow as Zoe/Joe

The setting for the play consisted of a grid of ladies' shoes at the back of the stage, with other pairs placed on cushions at the periphery of the stage. At various times, the shoes were used ingeniously to hammer in the message that sexuality was often a social construction, coloured by other factors like class and ethnicity. In one scene, Zoe reads personal ads from the insides of the shoes, where Asians invariably sold themselves as 'slim, smooth, submissive'.

But the strongest symbol used in the play was of the orchid itself: a flower enveloped by various myths and misconceptions. As much as the play sought to prune many of the exuberant fantasies we have about transgenders, the clearing of ideological foliage brought out the hidden buds.

In one scene, performed in blackout, we hear Zoe's voice scaling progressively higher as she makes love with Brian. At her peak we realise that it is Brian who has been performing fellatio on Zoe and not vice-versa. At moments like these, a few words come to mind to enlarge our understanding of transcultural and transgender experiences: transgressive, and truly, transcendent.

Date : 17 April to 13 May 2001

Venue : The Room Upstairs, 42 Waterloo Street, Singapore

TicketCharge Hotline : 296-2929 R(A) 18 years and above only

列印版本

列印版本

讀者回應

搶先發表第一個回應吧!

請先登入再使用此功能。