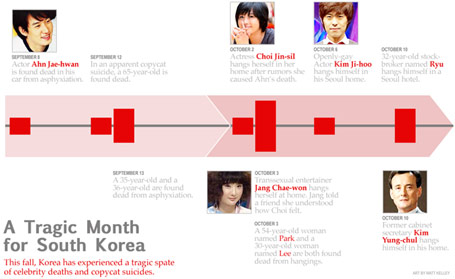

Click here to view enlarged graphic.

Even after his death, hateful comments were posted on Kim Ji-hoo's personal Web page. According to police, the 23-year-old model and actor hanged himself in his Seoul home on Oct 6. Labeled "one to watch", Kim's modeling and television career came to an abrupt halt after he disclosed he was gay on South Korean television.

On Apr 21, Kim appeared on the cable reality program, Coming Out. The groundbreaking show profiles the lives of gay Koreans with advice proffered by its hosts. But shortly after the episode aired, Kim's Web page was inundated with attacks on his sexual orientation. In addition, his modeling and television appearances were cancelled and his management company refused to renew his contract. In an apparent suicide note, Kim wrote: "I'm lonely and in a difficult situation. Please cremate my body."

Kim's suicide was the fourth by a South Korean entertainer in only a month. On Oct 2, Choi Jin-sil, the 39-year-old actress described as Korea's "national sweetheart" was found dead. Reports say that Choi was distressed by rumours on Web sites and in online magazines called jjirasi portraying her as an aggressive loan shark responsible for another actor's recent suicide. A frequent target of the online rumor mill throughout her career, in a July interview with MBC Choi said that she "dreaded" the Internet.

The "Republic of Suicide"?

According to the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), South Korea has the highest suicide rate among its group of industrialised nations. In 2007, there were 21.5 suicides per 100,000 people in Korea, compared with 19.1 in Japan, 10.1 in the United States and 6.0 in the United Kingdom. In fact, suicide is the leading cause of death for 20- and 30-somethings in Korea, which has some calling Korea the "Republic of Suicide."

Experts are unsure why the nation's suicide rate has increased 90 percent in just a decade. Financial problems and pain associated with disease and old age are partly to blame. But some think the stress of the nation's rapid modernisation is a factor. Pressure to perform in school and at work can lead to depression. But in Korea, cultural barriers often discourage mental health treatment.

Choi Byong-hwi, a Seoul-based psychiatrist, says that only seven percent of Koreans with mental health issues seek professional assistance due to "significant taboos attached to the treatment of depression in a psychiatric clinic."

In the absence of professional help, many are going online instead. South Korea has one of the world's highest rates of Internet penetration. According to figures provided by internetworldstats.com, 71 percent of Koreans use the Internet, compared to 74 percent in Japan and the US, 70 percent in Hong Kong, 59 percent in Malaysia and Singapore and 19 percent in China. Korea also boasts the highest rate of broadband access (80 percent), and nine out of ten 20-somethings have personal Web pages, or "mini-homepy", on social networking sites like Cyworld.

A recent article in the International Herald Tribune described how South Korea's active Internet culture is connecting suicidal people with "how-to" information and each other. An analysis of the media reports of 191 group suicides conducted between 1998-2006 found that almost one-third used Internet chat sites to form their pacts. A similar phenomenon has occurred in Japan and Australia.

Nasty Netizens

A malicious online rumour mill is also wrecking havoc in Korean cyberspace. According to the Cyber Terror Response Center of the National Police Agency, there were 12,905 cases of Internet violence in 2007, up from 4,991 in 2003. Although existing law punishes the crime of "aiding suicide" with up to 10 years in prison, most convictions result in only fines.

In several examples, the punishment doesn't seem to fit the crime. For instance, in 2005, 30-year-old accountant Kim Myong-jae became public enemy No. 1 after rumours circulated online that his abuse precipitated his girlfriend's suicide. Although these claims were not substantiated, Kim's phone and e-mail were inundated with death threats. After calls were issued to boycott his employer, he was forced to quit his job and drop out of school. In August, a court ordered 50 journalists and Web users to pay 2 million won (USD $1,500) in fines for spreading false rumors against him.

According to the psychiatrist Choi, the perpetrators of what's called "cyberviolence" in Korea are typically immature, aggressive and poorly socialised boys and young men who may not grasp the consequences of their behaviour. Not surprisingly, Korea's few openly queer celebrities are a frequent target.

When Ha Ri-su, the popular 33-year-old transsexual singer, model and actress was the target of Internet attacks, she pursued her libelers and filed a police complaint against a 30-year-old man who reportedly posted defamatory comments like, "those who like Ha Ri-su are not human" on her Web site and fan sites.

The late transgender entertainer Jang Chae-won, also known as "second Ha Ri-su" also became the focus of online criticism. When she appeared on the SBS television program Truth Game last May, Jang who was then 25 told viewers that she had undergone sex reassignment surgery since first appearing on the show in 2004.

After her second appearance, Jang enjoyed a modest following after hundreds of thousands of people visited her Cyworld homepy. Although police attributed her suicide to despondency after breaking up with her boyfriend, reports suggest that online harassment may have played a role in earlier suicide attempts.

An unexpected opportunity

On Aug 31, which was World Suicide Prevention Day, South Korea's Ministry of Health, Welfare and Family Affairs unveiled a five-year plan to reduce the nation's suicide rate by 10 percent by 2013. Efforts ranged from improving the social safety net for the poor and elderly to erecting screen doors at subway stations to prevent jumpers. Sixteen people have already committed suicide in Korea's subways this year.

The rash of recent suicides has certainly underlined the need for such a plan. However, it has also focused attention on LGBT Koreans by integrating their experiences into a "mainstream" conversation.

On Oct 9, Hong Seok-cheon, the co-host of Coming Out, appeared on the MBC program, "100-Minute Debate." As Korea's first openly gay actor, he was invited to help viewers understand what may have driven Kim and Jang to take their own lives. Hong said that both he and Kim suffered "numerous discriminations" as openly gay celebrities, and he criticised the government for failing to heed previous calls to address cyber violence.

Although the government has as yet been slow to act, it is now politically expedient to do so. Members of the ruling conservative Grand National Party (GNP) are introducing the so-called "Choi Jin-sil Act." The proposed legislation aims to toughen prohibitions against cyber slander and expand the use of resident registration numbers (Korea's national I.D. system) online. Furthermore, for one month, 900 agents from the Cyber Terror Response Center are scouring the Internet looking to arrest those who "habitually post slander and instigate cyber bullying."

Critics say the law's actual intent is to control one of the opposition party's most powerful forums - the Internet. Shortly after taking office in February, rumours about the safety of US beef imports spread virally over the Web. For many weeks, massive protests paralysed downtown Seoul and forced Lee Myung-bak's cabinet to resign. But President Lee's efforts to regulate the Web are buoyed by citizen sentiment. Unlike citizens of most countries, polls suggest that a majority of South Koreans support censoring some forms of speech online.

Rather than seeking to eliminate online anonymity, Korea's LGBT leaders are advocating for institutional protections. Hong is against the President's proposal, saying it goes too far, and Lee Jong-Heon of the gay human rights organisation Chingusai ("between friends") referenced the removal of gays and lesbians from an anti-discrimination bill as proof that the human rights of sexual minorities were being ignored. The bill, which was drafted during the previous administration, generated significant controversy and has since languished.

Of course, after 11 deaths in 33 days, everyone's first objective is to stop the suicides. But Lee and others are hopeful that the public's grief may also foster an environment that's more sympathetic to an institutional safety net for Korea's sexual minorities.

Matt Kelley is a gay mixed-race Korean-American living in Seoul. He is currently writing a book about the intersections of race and sex in Korea. His website: www.mattkelley.info. Mike Lee is a student who also lives in Seoul.

列印版本

列印版本