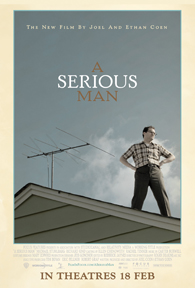

The similarities are striking: A Serious Man is also an existential comedy and a morality play. Its protagonist, a Larry Gopnik who lectures physics in university, is placed in a Job-like situation where anything that can go wrong will go wrong, and get worse because he pushed to make a moral choice that he may not even comprehend. And yes, this is a comedy.

On the domestic front, his wife is about to leave him for his best friend and neighbour, who is such a nice guy that he might just convince Gopnik to vacate the house to them. His son is in danger of flunking Hebrew school and botching his bar mitzvah while his almost autistic brother is writing some kind of kabbalistic mathematical treatise while hanging out in gambling dens and gay bars. Professionally, Gopnik’s tenure hearing may blow up if the committee should know of a student who is simultaneously trying to bribe and blackmail him. And financially, a mysterious Columbia Record Club wants to bill him most handsomely for a monthly subscription he’s never heard of or received.

Oy vey! What’s a decent man, an innocent man to do when the universe seems to make him the butt of some obscure joke? The piling on of injustice after injustice takes a mystical significance: Why me? What’s wrong with the moral underpinnings of this world if an innocent man is made sport of? What is the universe trying to tell me? And why does no one seem to offer good or even comforting advice?

The Coens take advantage of the 1960s Jewish-American millieu of this film to sharpen the moral bewilderment and cruel irony that face our protagonist, the meek Everyman – and thereby avoiding the kvetching and slapstick self-deprecation that marred a few moments in the Woody Allen film. Their film is far more of a dark comedy that isn’t played for guffaws, just as philosophical as Crimes and Misdemeanors, and are perfect explanations for a comedy as a series of bad things, perfectly timed, happening to someone else.

列印版本

列印版本