Few forces in cinema are as potent and all-consumingly powerful as sad kids, or so moviemakers like to think. For some reason, this week sees two movies involving sad kids in crapsack worlds from two very different cultures, the other one being Let Me In, of course. But maybe there is a point, and it stems from our culture’s perception and idea, and a pretty good one at that, that really really horrible things should not deserve to befall our children, because the children are our future.

Of course, the real world does not prevent children from often experiencing tragedy that is outsized and out of proportion to their capacity to comprehend and struggle against. In general, this does not make for a good film. Like it or not, audiences expect things from cinematic narratives – if not redemption, catharsis; if not a quest fulfilled, a narration they can gleam some overall meaning from. And this is why sad films about sad children engage with and even shock audiences by consciously attacking our assumptions about the responsibilities and duties of society and state.

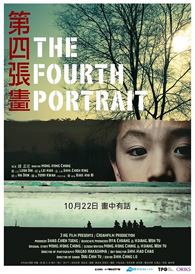

Mong-Hong Chung’s The Fourth Portrait tries only the first half of this time-tested formula, to a mixed bag of occasional successes and often sharp disappointments. As expected it starts with the most fundamental loss to children imaginable, in this case the loss of a parental figure, leaving pre-adolescent Xiang (Bi Xiaohai) an orphan. There are several adults he can look for as surrogate parents, but none fit the bill that exactly. There’s the hard-bitten school janitor, a man who shares with Xiang various anecdotes about surviving World War II but nothing useful to surviving awful home lives; his birth mother (Hao Lei), a hostess and sometimes whore who immigrated from the mainland; a ne’er-do-well thief and conman (Na Dou) just fired from this job in real estate and has no real prospects to speak of; and his stepfather, a complete jerk (Leon Dai).

None of them are, of course, satisfactory in terms of meeting the parental needs of our protagonist. None of them will provide him the mix of love, guidance, care and wisdom that a good parental figure requires, and it is up to our hero to carve out a path for himself in a loveless world to survive.

Not a single relationship is ever developed to its full because probably for director Chung, none of them can be and the whole point of the film is that you can only rely on yourself in the end. This is developed in a roundabout, dreamlike manner in which nothing is resolved, with no catharsis, no resolution and no point. No themes of class and politics are ever touched on despite the ample opportunity given for example, by the birth mother, whose own hard luck story of coming from the mainland is revealed to have made her much of what she is, or the ne’er-do-well thief who thinks himself a big shot but is really a sweet, lovable, ordinary man.

Despite its wins at film festivals worldwide, The Fourth Portrait was for this reviewer a draggy, uninvolving experience; a series of pretty pictures and occasional good performances and well-constructed moments, all of which don’t add up to say anything of meaning. It’s like watching someone relate a dream. And while the movies can be said to be man-made dreams, the fact remains that most of the time people aren’t interested in what you dreamt about last night. He foresees a very short run in theatres for this film.

列印版本

列印版本

讀者回應

搶先發表第一個回應吧!

請先登入再使用此功能。