But there are cases when people are made to abandon their birth ethnic identities for a better life. In any corner of the Western world one would frequently find "bananas" all around in the form of the adopted children of white parents who are Asian only genetically. Should any of the older Chinese elite Singaporeans meet these "bananas" one can only perhaps imagine their consternation at first. They might think they were seeing ghosts. They might not be wrong. Some of these orphans were of course adopted in infancy, a number are picked from their orphanages that dot the globe that they are placed when they are abandoned. In a curious way, they have had to die with their old lives to be reborn in the West, with these orphanages forming a sort of limbo between a purgatory and a womb: how do these orphans deal with the ending of their old lives as they start to prepare for the new ones that may lie ahead?

French Korean director Ounie Lecomte is herself one of these "bananas" herself. A Korea-born, French-raised filmmaker who now attempts to return to her roots and her own purgatory.

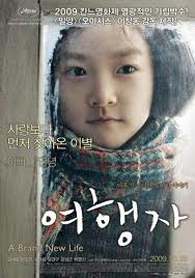

Jin-Hee (Kim Sae Ron), is put up for adoption at a Catholic orphanage in Korea by her father, for reasons that she does not know. She passes her days mostly in a deep, funereal silence, refusing to love anyone else but her father that she seems to know deep down is never coming back. Sae Ron joins such great child performers like Victoire Thivisol (Ponette), Jodelle Ferland (Tideland) and Brigitte Fossey (Forbidden Games) in playing a child for whom fun and games are not just fun and games, but a process of going through and dealing with a larger and more horrible reality she does not yet quite comprehend.

Beautiful camerawork and finely observed long takes bring you deep into Jin-Hee's psyche, revealing unto you the depths of her character (such a finely wrought scene with a doctor). Her friendship with Sook-Hee, a much savvier orphan who is doing everything she can to get adopted, such as being able to speak English, forms the emotional core, and seeing the two girls in scenes involving the care of a sick bird and sneaking pieces of cake is a delight not for just its lack of sentimentality, but also the film's overall tough-mindedness. Lecomte subtly transforms a tale of a young girl's abandonment into a Catholic tale of the purgatory of abandonment, the limbo of waiting, and the possibility of rebirth.

Sometimes, one does indeed need to die a little, in order to live again.

Printable Version

Printable Version

Reader's Comments

Please log in to use this feature.