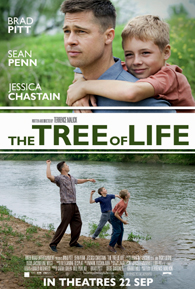

The Tree of Life is his most ambitious film yet and plays like two of my favourite poems wrapped around each other: This Be the Verse by Philip Larkin and Auguries of Innocence by William Blake. It possesses a scale, depth, and ambition that can be only compared to 2001: A Space Odyssey but with a sense of human feeling and emotion well missing from Kubrick’s oeuvre.

It is ostensibly the story of Jack O’Brien (Sean Penn), framed against his childhood in Texas and even further, the wider scale of the universe. Jack, like all of us, is born. He is delivered into innocence and wonder. He has a mother and father. He has a brother. He loves and is loved. He faces up to the imperfections of human love, which is inevitably shot through with fear, deceit and manipulation, which he learns. He ponders the vastness and unfathomableness of Creation. He grows up.

Jack, like all of us, is the end product of a long series of inexplicable chances and coincidences as well as a series of decisions he has made. He questions fate, he questions himself, and he arrives at reconciliation.

Out of one single solitary life, Terrence Malick wrings the story of every man, woman and child that has ever lived on this planet. It puts our lives on trial almost in the manner of a procedural. It begins with a question, followed by an investigation, followed by a verdict, followed by a sentence, followed by a reconciliation.

Yet Malick approaches such grand and noble themes, telling them in the most mundane of settings with a mastery of the film medium that is truly to behold. There is a scene involving an airgun that is one of the most powerful moments I have beheld onscreen this year: the message it conveys being that when you learn to mistrust even those who you thought could never hurt you, you die a little inside.

The performances are excellent, and Jessica Chastain is a great new discovery; she and Brad Pitt are excellent as the parents. Mom (the parents are never named in the film, just as they never are when you’re a child) seems to be an idealized version of the pliable and understanding matriarch, whereas Dad appears to be the controlling, unreasonable and authoritarian father figure. Yet the film does show both as equally responsible for scarring Sean Penn’s character, one through her pliability, the other via his unreasonableness. Never have I seen a film more accurate in evoking the painful ironies of parental love and the inevitable transference of fear to one’s children it entails. As Larkin said, “they (expletive) you up, your Mom and Dad”, indeed.

Still, against the vastness of creation, Malick holds up the possibility of reconciliation in a manner that is neither sentimental nor mawkish. Creation, Malick seems to say, is perfect because it doesn't want to inspire fear or love in us (even if it does), neither does it want to control us, it just is, and it is perhaps in its wonder that we may find the strength to forgive and move on. It’s a beautiful message; and Malick has conveyed it with a poetry-in-motion picture of everything that has only mattered.

Printable Version

Printable Version

Reader's Comments

It is just plain weird, someone, somewhere is smoking something.

..................."the only way to be happy is to love"

Excellent movie :)

Please log in to use this feature.