In a judgement dated 15 March 2011, High Court judge Lai Siu Chiu dismissed the first appeal relating to the constitutional challenge against Section 377A of the Penal Code. This is the law that makes “gross indecency” between two men an offence punishable by up to two years’ imprisonment. The challenge was filed by Tan Eng Hong, who was last year charged under this law after he was caught in a shopping centre toilet with another man.

Represented by M Ravi, Tan’s challenge is still at the procedural stage. Ravi intends to appeal against Justice Lai’s dismissal, so this is nowhere near the end of the story.

Readers will probably need to have the background refreshed.

Background

The incident that resulted in two men, Tan and Chin, being caught in a shopping centre toilet was recounted in the article The 377A hide-and-seek. Both men were charged under Section 377A. On 24 September 2010, M Ravi, acting for Tan, filed an Originating Summons challenging the constitutionality of this law. Mid-October, the Attorney-General’s Chambers (AGC) withdrew the 377A charges, substituting charges under Section 294 (obscene act in public) instead.

On 10 November 2010, Chin pleaded guilty and was fined S$3,000. In mid December 2010, Tan too pleaded guilty to Section 294 and was likewise fined S$3,000.

However, since the constitutional challenge to Section 377A had been filed, it still needed to be dealt with on a separate track. At a hearing on 7 December 2010, the Assistant Registrar agreed with the Attorney-General’s application to strike out the case. Tan then appealed to the High Court to reverse the Assistant Registrar’s striking-out decision. The latest decision from the High Court was to affirm that striking out order.

The decision by Justice Lai

The judge framed the issue before her in terms of two main questions (there were two lesser questions):

1. Does Tan Eng Hong have locus standi? That is, is he affected by this law to have a legitimate interest in the issue?

2. Is there a real controversy that requires the court’s attention? Here, the term “real controversy” is used in a way different from ordinary language. It simply means: Is there a matter of importance to be decided by a court?

In a nutshell, the judge found that the answer to the first question was a Yes and to the second question, a No. Thus the Assistant Registrar’s striking-out decision was reaffirmed. It’s a highly technical decision, and for this post, I shall only touch on the key points in laymen’s language. The full text is archived here, thanks to M Ravi.

Locus Standi

On the first question, the court rejected the AGC’s contention that since the original 377A charge had been withdrawn, Tan had no further interest at stake. The court stuck to an established principle that “a citizen should not have to wait until he is prosecuted before he may assert his constitutional rights.”

The court also found that there is a real question as to whether Section 377A is constitutional. It reminded itself that constitutionality is to be tested on two measures: (a) whether “the classification [implied by Section 377A] was founded on an intelligible differentia”, and (b) whether “the differentia bears a rational relation” to the purpose of the law. [Note: this was better explained in the earlier post The management of gays, part 1; see the discussion about page 340.] Insofar as Section 377A criminalises male but not female homosexual intercourse, Tan’s constitutional rights, specifically in relation to Article 12(1) of the Singapore Constitution (“All persons are equal before the law and entitled to the equal protection of the law”) might be said to be called into question.

Since there is a constitutional question and Tan as a practising homosexual is at risk of being prosecuted in future (even though the previous charge was withdrawn), the court ruled that he had locus standi to launch this case.

Is there a controversy?

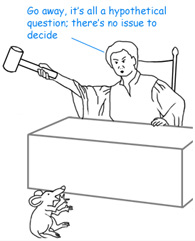

Then, in a shockingly opaque portion of the written decision, the judge declared that there was no “real controversy” for the court to settle. It said that “the facts are merely hypothetical”. But of course if one does not have to be prosecuted to launch a constitutional challenge, then naturally the facts are hypothetical, but there are precedents that establish that if the matter is serious enough, it is still a real issue that needs to be decided.

Choo Zheng Xi, who is legally trained, did not think it was logically consistent for the court to say that “that a person can have locus standi but that there is ‘no real controversy’”:

If Justice Lai accepts in para 20 that constitutional rights can be infringed by the spectre of future prosecution, it must naturally follow that there would be a real controversy despite the fact that charges against Tan Eng Hong have been dropped.

Professor Michael Hor from the National University of Singapore’s Law Faculty, opined likewise:

It seems to me that the two propositions are contradictory. The judge found that he had locus standi, essentially on the basis that he should not have to wait to be prosecuted before he may gain access to the court to decide on his constitutional rights. The judge then went on to say that there was no real controversy because the prosecution against him had been withdrawn. The two holdings are contradictory — if he cannot now be heard on the constitutionality of 377A (because the prosecution had been withdrawn) then he will have to wait until he is prosecuted in the future for 377A conduct before his constitutional rights can be determined. That was precisely what the first holding said he should not have to wait for.

It is possible that Lai’s hopelessly confused writing obscured the point that she might have been trying to make: That there was no real controversy for her court to decide. I say this because immediately following the “no real controversy” finding was an entire section discussing a separate procedure. Under this procedure, individuals “can request the President to refer the issue to the Constitutional Tribunal under Art. 100 of the Constitution.”

Yet, as Hor says,

The problem with this is that there is nothing to guarantee that the President will agree to do so. In any event, it appears that there is every likelihood that the reference procedure is only for constitutional disputes between the different organs of state — e.g. President disagrees with Cabinet. The Judge herself says so.

Choo was equally puzzled, especially with Lai saying all this:

while noting Chief Justice Chan Sek Keong’s extra-judicial view in an [Singapore Management University] lecture that Article 100 of the Constitution does not apply to hypothetical disputes. It is more likely than not that CJ’s view is correct: an Art 100 Constitutional reference by the President has been said by the government (Lee Hsien Loong when he was DPM) only to be exercisable at the initiation of the government. This was cited by CJ Chan in an academic article in 1996.

The long and short of the logic of para 26b of this judgment is this: in practice, an individual might really have to resort to breaking the law to have his rights vindicated. How would one be expected to go to the President for a Constitutional Tribunal if the President can only apply for one to be convened if initiated by the government? Would this ever actually happen in reality, considering that if a potentially unconstitutional law were to be challenged, the government would obviously have an interest in not seeing it challenged?

Further, the powers of relief the courts have are substantively different from those of a Constitutional Tribunal: the latter is only empowered to render an opinion, whereas the former can issue declaratory relief or injunctive relief, amongst other remedies.

What Tan wanted was not an opinion from a tribunal but a declaration from a court that has the force of law. The Article 100 procedure is no substitute.

What has provenance of the law to do with anything?

M Ravi, in his submission, referenced the William Leung case from Hong Kong, when Leung successfully challenged the territory’s law that discriminated against gay men in age of consent. I’m not sure exactly what was said in his submission, but it would likely be that this was to show an example of a court holding that such discrimination against homosexual persons violated the principle of equality.

Contesting this, the AGC argued before the court that this example was irrelevant for the Singapore courts to consider, because Hong Kong’s constitutional Bill of Rights was an incorporation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, a treaty that Singapore had not signed.

Lai appeared to accept this argument. But it makes no sense. Indeed, Hong Kong may have taken the text from the ICCPR, but once incorporated into Hong Kong’s Bill of Rights, it is domestic Hong Kong law, not an international treaty at work, so whether Singapore has signed it or not was immaterial. Although from a different provenance, Singapore’s Constitution has similar language about equality under the law.

As Hor says,

the difference in the formal source of constitutional law has no bearing on whether a citizen can ask the court to determine his or her constitutional rights.

* * * * *

In affirming the Assistant Registrar’s decision to strike out the Originating Summons, Lai awarded costs to the AGC. Tan will be required to pay up, though it is not immediate if, as intended, the matter is appealed further. Personally, I wonder if Tan was aware of his unlimited financial liability.

I am sure I’m not the only person in Singapore to believe that no judge relishes the burden of having to decide on the constitutionality of Section 377A when it is such a political hot potato. This latest court decision does not shake my belief.

Nevertheless, Hor reminded me that there are two silver linings:

a) the holding in favour of locus standi because of potential prosecution

b) the holding that it is an arguable case that Article 12 [of the Constitution] is infringed because “there is no social objective that can be furthered by criminalising male but not female homosexual intercourse”.

Alex Au has been a gay activist and social commentator for 15 years and is the co-founder of People Like Us, Singapore. Alex is the author of the well-known Yawning Bread website.

列印版本

列印版本